Listen to this story:

Christchurch is not often considered the site of one of the nation’s geological wonders. It lies on a flat river delta, on plains that sprawl west and south and a vast coastline that arches north.

But turn south-east and you will see the Port Hills rising steeply above the city, the grand remnants of the Lyttelton volcano crater, eroded and battered for the past eight million years.

Lyttelton Harbour is the home to Christchurch’s port, the area’s highest peak plus a number of hiking landmarks positioned around the crater rim.

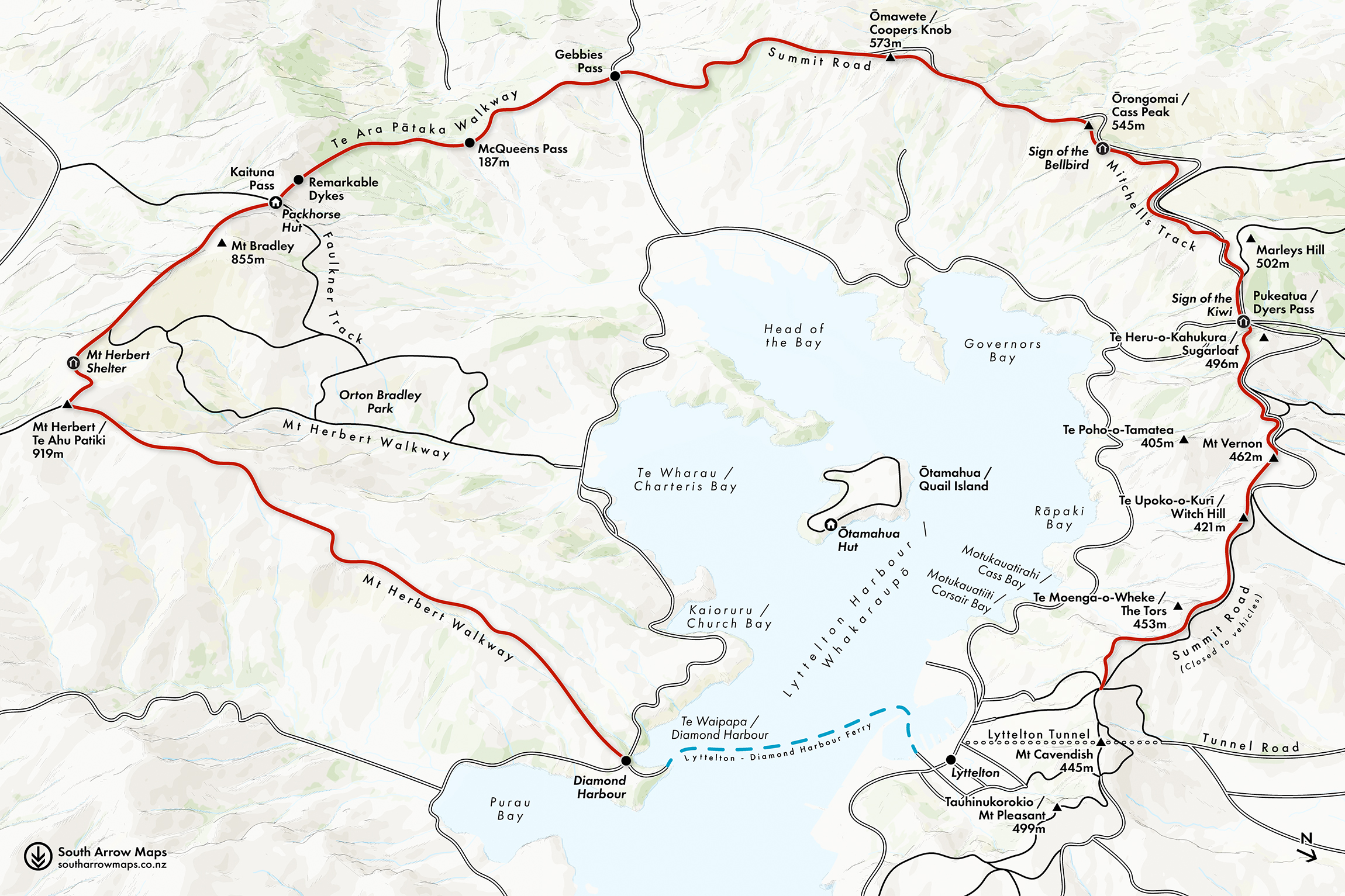

Every winter a group of enthusiasts run a 53km ultra race around the rim of Lyttelton Harbour, starting at Diamond Harbour and finishing at Hansen Park in Christchurch. Christchurch Tramping Club tackles a similar route in an annual walking marathon.

A technical challenge the crater rim is not, but the task of walking or running 40–50km of trail in a day is substantial, even if you’re a hardcore tramper.

Having recently moved back to Christchurch, I decided to make the crater rim my primary tramping challenge. I would start in Diamond Harbour and work my way around to Lyttelton. I had done most of this route in sections and knew much of it was exposed tussock and farmland, which meant the weather was an important factor.

On the crater rim route, if the wind gets up, rain comes in and the temperature drops, it’s easy to throw on another layer. But with next to no shade along the way, the sun can also make this route pretty uncomfortable.

From the starting line on the rocky beach at Diamond Harbour I could see the finish line at Lyttelton a mere 3km away, directly across the water. It would be over eight hours before I was that close again.

The flag dropped at sunrise and I was straight into the major ascent of the route: a 919m climb to the summit of Mt Herbert, the highest point on Banks Peninsula. Unfortunately its magnificence is lost somewhat on account of three factors. Its drawn-out, racked western face takes the summit a long way back from the harbour rather than towering directly over it; it’s largely devoid of flora and fauna; and unlike some of the more heroic-looking peaks around the crater rim that feature clusters of jagged basalt bursting through their grassy skins, it has a rounded, blobby profile.

Nevertheless, 919m is a reasonable ascent for the beginning of a 40km day hike, so I pressed to get it done sharpish, without over-exerting, and was pleased to cover the 7.7km section in less than two hours.

From the top, the clear view across the harbour basin was juxtaposed with the fog that hung over Christchurch. It was like looking at the world through a misty windscreen.

Although I enjoyed the 360-degree vista from Mt Herbert, part of me felt sad at the absence of native forest in the area. Māori destroyed roughly a third of it pre-colonisation; the remainder was logged or burned by European settlers, and the land’s been grazed for over a century. There are numerous private and community planting projects underway, however, so there is reason to feel optimistic for the future.

The going was moderately easy from Mt Herbert and became a matter of chewing through the kilometres. The next point of interest was the nine-bunk Sign of the Packhorse Hut. This involved skirting around and then zigzagging down the southern flank of Mt Bradley.

Being on a southern hill face and sheltered by a native canopy, the track briefly became muddy before descending to the red-roofed hut, which looked magnificent perched on a sunlit saddle against a backdrop of mist flowing up Gebbies Pass.

Built in 1919 from local stone, Packhorse Hut forms part of the rest-house network that extends from Sign of the Takahe in Cashmere. This network was the brainchild of politician Harry Ell (1862–1934), an ardent naturalist and conservationist who wanted to preserve what was left of the native flora on the Port Hills.

Ell had a grand plan for a summit road to run from Godley Head to Akaroa via Gebbies Pass, with a total of 14 rest houses along the route. Although he did not see the plan fully realised, over time it has essentially come to fruition. The Crater Rim Walkway runs 27km from Godley Head to Ahuriri Reserve, and is linked to the 35km Te Ara Pātaka track by a section of Summit Road above Governors Bay.

Ell managed to construct four shelters: Sign of the Takahe, Sign of the Kiwi, Sign of the Bellbird and Sign of the Packhorse. Rod Donald Hut also sits along the Te Ara Pātaka route near Waipuna Saddle and, in spirit at least, adds to Ell’s vision.

From Packhorse to Gebbies Pass, my route passed through forestry plantations in varying stages of maturity, and although this section is reasonably popular, I encountered surprisingly little foot traffic.

Gebbies Pass served as a convenient halfway marker, and with that in the rear view mirror, I was feeling good. But the feeling soon dissipated. The 4km Summit Road section to Ahuriri Reserve felt more arduous than I expected. I was 23km and over five hours in at this point – the fastest runners of the ultra race would have finished by now – and I had not stopped since the Mt Herbert summit. A lunch break was certainly in order and I had a short rest.

The mist coming up Gebbies Pass was spilling into the harbour basin, and when I set off again I was surrounded by cloud. I managed to escape it before reaching Sign of the Kiwi, but for the rest of the day it chased me up the harbour.

Governors Bay now sat far below me to the right; Sign of the Bellbird was close by on the left. Completed in 1914, it was the first of the four rest houses to be built. Although it is now a humble shelter, it was initially a cottage for caretakers of Kennedys Bush, the reserve in which it sat, and soon expanded to include tearooms. It even offered a short-lived post office service.

During the mid-twentieth century, however, Sign of the Bellbird was closed, abandoned and even partly dismantled. What remains is thanks to the durability of its stone construction more than anything else.

On a prominent rocky peak nearby stands the Cass Peak radar with its 13m dome. Built in the 1990s, it is used to track aircraft for almost the entire length of the South Island’s east coast.

There are many points of natural and manmade interest along this section, but this segment was my least favourite because the track itself is a tad overgrown in places. Perhaps it was also because this was where weariness started to kick in.

Sign of the Kiwi seemed to come quickly, however. Unlike the Bellbird, Sign of the Kiwi still thrives today as a bustling hilltop café visited primarily by throngs of walkers and gangs of cyclists. Queues often extend out the door.

I continued towards Sugarloaf Scenic Reserve where, for the third and final time, I headed into a section of track covered by native bush.

I had walked this section before and knew there wasn’t far to go – and just as well. Over 30km of hill walking was making hereditary knee issues flare up and the walk was becoming something of a chore.

I enjoyed the final section that follows the Summit Road above Cass Bay. The road has been closed to cars since the 2011 earthquake and I mostly had it to myself. The sun was dropping, but even my long shadow offered only intermittent company as the sun fought a losing battle against the tide of cloud moving up the harbour.

After 9hr 17min and 39.3km, I reached the top of the Bridle Path – my finishing line and the final piece of history for the day. Short and sharp, the Bridle Path allowed the first European settlers to travel between Lyttelton and Christchurch.

No doubt there was a sentimental moment to be had here. I could have sat quietly for a few minutes contemplating this 175-year-old route and the settlers who used it. But I knew there was a roast chicken in the oven at home, so I hurried down into Lyttelton to catch the ferry back to Diamond Harbour.

You, on the other hand, can head the other way down into Christchurch or continue on to Godley Head if you wish. That is up to you.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us