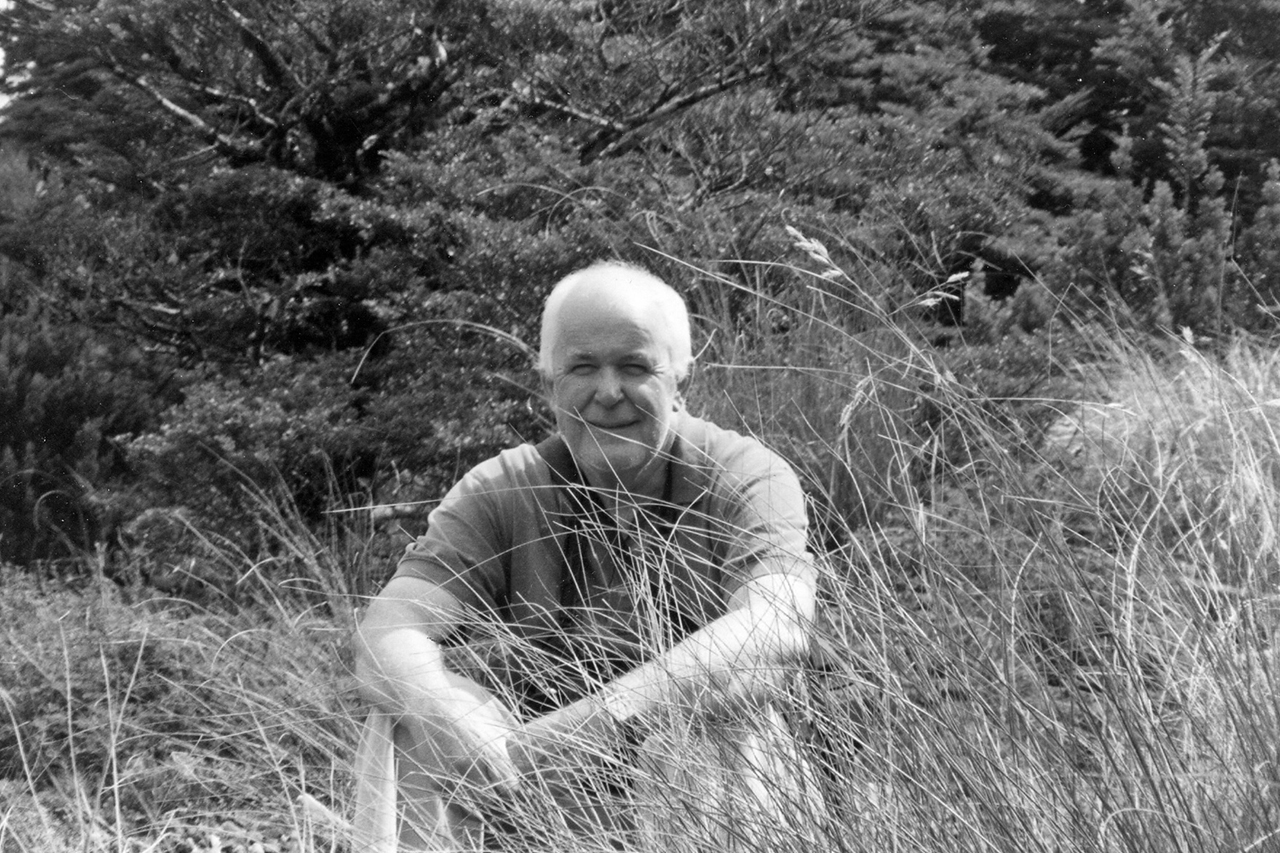

During his life, author and environmentalist Alan Froggatt has seen many changes to New Zealand’s wild places. His new book Great Stories of New Zealand Conservation highlights 50 projects created to protect the country’s environment.

It seems that conservation has been part of your life for a long time?

I have been a long-time member of the Forest and Bird and Kapiti Restoration and Maintenance societies. Also, Birds New Zealand and the Pukorokoro Miranda Naturalists Trust, and have planted my fair share of native trees. I’ve travelled from Bluff to North Cape several times and seen tremendous degradation to the environment. In places where I ranged as a kid, there are no longer trees of any sort and some of the rivers are now so polluted that you can’t swim in them anymore.

What sparked your determination to highlight this threat?

One of the triggers was a neighbour who was a key figure in the Save Manapouri campaign. This was a cornerstone in alerting people to the dangers facing our environment. On retirement, I became a keen birdwatcher and photographer and then wrote a couple of books about New Zealand birds. It involved a great deal of research, which I enjoyed, so then I thought: ‘what’s next?’

So, was there a particular aim in writing your book?

There’s a lot of misinformation about conservation; what has happened and why. We need to realise the importance of protecting our environment and understand that once we’ve lost something it’s gone. This has happened in the past and highlighting examples may alert people and motivate them to look after what we have left.

Would you like to mention any particular project?

The Kaitawa Reserve outdoor classroom at Paraparaumu. Initially, it was a desolate wasteland, in danger of urban development. The Kapiti Coast District Council was persuaded to turn it into a nature reserve where school groups can visit and learn about the local history, connection to tribal groups and link the biodiversity of the area to the school science curriculum. It is an innovative vision which is fulfilling its promise.

Do you have hopes for the environment?

No, and mainly because of population growth. When I grew up we had a population of 1.5 million, and now we’re knocking at six million and there’s very little control on numbers on the tracks. And there’s an attitude that some people have to ‘do’ a walk as a box-ticking exercise, without really appreciating the environment. But I do think a great many still also get in touch with nature.

What would you like to see happen?

The people at DOC have many different responsibilities, but they need to be more careful with how they protect the important remnants of the bush. Somehow regulate tourist numbers, which have seriously impacted some of our key walks. I miss being able to walk through the bush with a couple of friends, assimilating what I’m seeing and feeling. Now it’s noisy and crowded and many of the popular tracks are littered with rubbish and that’s sad.

It seems people degraded this country as soon as they arrived?

To the European settlers, it was all about ‘civilising’. New Zealand was a hard place in which to become established, so they had to use what resources they could to survive. And, out of ignorance, they brought significant pests with them. Sometimes deliberately, sometimes not. These new predators found paradise.

What message does your book have for readers?

Perhaps to get involved in some way with local conservation. Get engaged in protecting what we have left. It’s good for the soul; none of us live without the environment impacting upon us in some way.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us