When my wife Ali saw Kotepato Hut come into view, she burst into tears. After hours of dragging a heavy pack through the tangled, unforgiving bush of Te Urewera, anyone might have. But to her, the hut meant something far deeper.

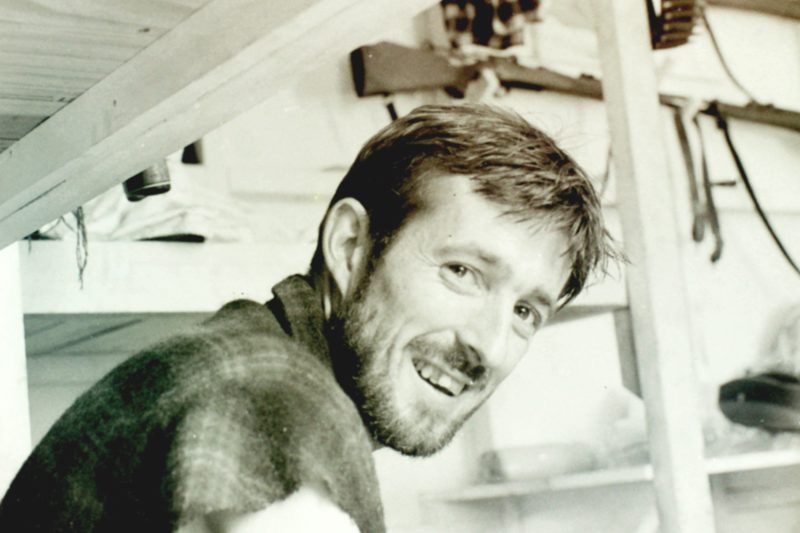

Ali carried a weight that couldn’t be measured in kilos. She is Tony ‘Slim’ Shaw’s only daughter, and had nursed him through the final two months of his battle with aggressive bladder cancer. This wasn’t just any tramp – it was a pilgrimage to the hut her father had built in 1968 with his own hands.

Our trip didn’t happen by chance; it took plenty of preparation. Before setting foot on the track that would lead us back to her father’s legacy, we had a few important calls to make. The Eastern Bay of Plenty DOC office directed us to Nga Tapuwae-o-Tāneatua Tramping Club, which helps maintain Kotepato Hut. Club members generously offered guidance and suggested contacting Bob and Mary Redpath, owners of Wairata Station, to request permission to cross their farm and park near the track’s start.

The Redpaths were warm and welcoming, clearly proud of the history woven through their land and its enduring connection to stories like Tony’s. They even offered us a car park beside their woolshed.

We’d been warned to keep a close eye on river levels. There are two crossings on the way in – the Wairata Stream and the Waiōweka River. If the Waiōweka flow gauge reads over 1.5m, it’s considered too risky to cross. We kept one eye on the gauge and the other on the forecast.

To reach the trailhead, we left Ōpōtiki and headed east along Waiōweka Road toward Gisborne. At Wairata we turned off, crossed the one-lane bridge and followed Redpath Road to its end, where we found the old woolshed.

A DOC noticeboard marked the start of our journey. Overhead, the sky hung low and moody, hinting at rain.

We reached the Waiōweka River crossing, where a pair of paradise shelducks startled and took flight upstream, honking loudly as if to trumpet our arrival. We’d been warned the start of the Kotepato Track was easy to miss, and it was. The marker was there, fixed to a rimu, but the leafy canopy hid it from view and we walked straight past.

After missing the track, we relied on GPS to guide us. We crossed the river, climbed a steep bank, and eventually picked up a faint, overgrown trail. Ponga fronds hung like curtains across the path and we pushed through, surrounded by a lush tapestry of native bush. Towering rimu, tōtara and kahikatea stood sentinel as we made our way along what soon became a well-marked track.

As we made our way through the bush, Ali talked about her father – how he used to spread his hunting gear across the lounge floor before a trip, carefully packing tins of food and explaining each item’s purpose. “I still don’t know how he carried it all,” she laughed. It was Tony who’d lit the spark in her for the outdoors – his curiosity about the bush, the birdlife, and the stories hidden in the hills now lived in her.

The bush was dense, vibrant and alive; a shifting kaleidoscope of green. Tūī swooped overhead, korimako chimed their melodic chorus, and curious pīwakawaka flitted at our heels. We moved slowly, pausing at each decision point to search for a new marker. There was no rush. Ours was a quiet act of remembrance. We were tracing Slim’s hunting ground.

The track led us up and over a low saddle then down into Te Pato Stream. And it was from the streambed that we first caught sight of Kotepato Hut. A short climb brought us to the hut, standing tall among overgrown grasses and ferns.

The trek had taken a little over two hours. We took our time to explore the hut.

Ali stood quietly at the doorway for a long moment before stepping inside. Her eyes traced the timber walls, the bunks, the hearth – every surface her father had touched.

“It feels like he’s still here,” she chuckled. Earlier, when she’d first seen the hut, the tears came fast, a flood of relief and memory. Now there was a calm, the kind that settles when you arrive at where you were meant to be.

Like most old deer-culler huts, Kotepato followed a familiar blueprint: plywood-lined walls, a stainless-steel bench, an open fire, a woodbox, four or six bunks and an aluminium basin outside. But Tony, a builder by trade, had added his own touch. He built six bunks, arranged in two stacks of three. The centre bunk had a hinged section that folded down into a seat big enough for three weary hunters to rest on. It was one of a kind. Pure Tony.

We discovered that the hinged seat was gone, replaced by a simple ladder leading to the top bunks. But the open-hearth fireplace remained and we made good use of it on what turned out to be an unusually cold summer day.

Ali climbed into her sleeping bag to warm up while I cooked our go-to tramping meal: Japanese ramen laced with chorizo and mushrooms. The fire crackled, the kettle steamed, and in that warmth and quiet it felt like a nod from the past, a small comfort in a place still humming with Tony’s presence.

Sitting by the fire, Ali traced her fingers along the wall. “This is the hut my dad built,” she said softly. “I can almost see him here – boots off, fire roaring, cooking a feed, proud as anything.”

To support deer cullers working deep in the backcountry, New Zealand Forest Service built a vast network of huts, bridges and tracks – infrastructure that still dots the backcountry today. Cullers were supplied with gear, food and shelter to make the brutal work just a little more bearable. The huts weren’t just places to sleep: they were lifelines. Kotepato Hut was one of them.

Deer culling wasn’t for the faint-hearted. It demanded grit – both physical and mental resilience – and Slim was regarded as one of the best. Landing a role as a deer culler was his dream come true. From 1962 to 1968 he lived in near-isolation in Te Urewera, shooting deer, building huts and bridges and cutting all-weather tracks. “Those were the good old days,” he’d say later, despite the toll it took. Arthritis in his feet was, he reckoned, the price of crossing freezing rivers and battling unforgiving terrain.

As the rain settled in, my thoughts drifted to stories from Tony’s time at Kotepato Hut. One in particular stood out: a week when miserable weather pinned a group of hunters down, cabin-bound and restless. By day seven Tony had had enough. He struck out alone and returned after shooting seven deer and a massive black-and-tan boar. No one else had made a haul like that.

Kotepato Hut operates on a first-come, first-served basis. The visitor book showed it’s mainly used by hunters, members of Nga Tapuwae-o-Tāneatua Tramping Club and volunteers from Eastern Whio Link, a volunteer conservation group working to bring whio back to local waterways through stoat trapping.

On this, the anniversary of Tony’s death, Ali and I were fortunate to have Kotepato Hut entirely to ourselves. The clouds lifted and parted and the stars put on a celestial show. The only sound was the crackle of the open fire. Surrounded by the raw beauty of the bush, we felt Tony’s presence in every beam and nail of the hut.

We rose early the next morning, feasted on bagels and eggs, gave the hut a good clean and restocked the woodpile. My final act was to erect a small plaque above the fireplace:

Kotepato Hut

Built by Tony ‘Slim’ Shaw

January 1968

In honour of Slim,

Deer Culler, New Zealand Forestry Service

His hands built it,

His spirit lives here.

Forever remembered.

At 6.30am we climbed down to Te Pato Stream, removed our packs and paused in the stillness. With only the soothing crackle and gurgle of the stream as our music, we held our own ceremony for Tony, returning a little bit of him to the place he loved so dearly.

We retraced our steps up and over the spur, lifted by a full-throated morning chorus. As we descended to the Waiōweka River we spotted the track marker that had eluded us the day before.

The river was low and so were the clouds, floating like candyfloss beneath the ridgeline. It was eerily calm, as if the bush itself had wrapped us in a soft blanket of comfort.

Kotepato Hut and the man who built it are forever etched in our hearts.

— Gerard Watt is a keen tramper and Land Search and Rescue volunteer with a deep respect for New Zealand’s backcountry huts, heritage and conservation efforts.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us