Home / Articles / Great Walks / Lake Waikaremoana

I am on the edge of Lake Waikaremoana in a basic wooden cabin. My cabin, shared with five others, overlooks the black waters of Opourau Bay. Groceries are being piled onto a round table and organised into daily portions. It’s mid-January and a mild 17 degrees outside. Black swans honk as they paddle across the lake. Thunder rumbles. Rain courses down the window.

Back in my Wellington city apartment, I dreamed of getting away to this isolated pocket of Te Urewera walking among giant podocarps. What I hadn’t banked on was the insight I’d get into the cultural shift taking place here as I wandered along the lake’s 46km trail.

Before heading north, I read about Tūhoe’s Treaty settlement in 2013 that granted Te Urewera personhood and ended Lake Waikaremoana’s status as a DOC-managed park. But I couldn’t really make out what it meant in practise. As a tramper, how should I act when I get there? Would it be different to other Great Walks? How would I know if I needed to do or think about things differently?

But I felt excited and started boning up on the history of Tūhoe and Lake Waikaremoana. Tūhoe, I learned, were now recognised in New Zealand law as kaitiaki (caregivers) of Te Urewera. Over time, DOC’s presence would taper away and Tūhoe would become full-time guardians of the Great Walk. Other things would change. Tūhoe would encourage people to start seeing Te Urewera less as a recreation estate managed by the government and more as a much-loved family member we’d all need to care for.

My plan for walking the track was simple. I would reflect on this world view as I traversed the landscape.

After an early morning boat ride on the lake, we make it to Onepoto to begin the gruelling climb through dense forest up to Panekire Bluff for lunch. Standing on the sheer rock escarpment with the sun on my face and my 12kg pack gleefully discarded, I take in the panorama, eat my cheese and crackers and try to make out the tragic shape of Haumapuhia in the distance. According to iwi, it is the body of their ancestor preserved in the rocks below. Defying her father’s wishes, she created the lake and hillsides first by thwarting his attempt to drown her, then by transforming into a taniwha, and finally by struggling to flee to the ocean as she turned to stone. I imagine how it feels to have such a visceral connection to the landscape.

By late afternoon, we made it to Panekire Hut. All 36 bunks are booked. Happy campers and their gear are strewn across the lawn as the sun begins to fade.

We start early the next day, taking in the fresh smell of the bush, the frilly shape of podcarp leaves underfoot and the flashes of brilliant blue sky above us. It doesn’t take much to free my mind of work and to simply enjoy putting one foot in front of the other. Passing a Tūhoe ranger in a high-vis jacket, we call out “kia ora” and ask about tomorrow’s weather. The sun’s still out when we reach Waiopaoa Hut so I strip off and take a dip in the lake.

We head up Waiopaoa Stream, cross grasslands and walk through a changing landscape of kānuka and rimu forest. Before we reach Marauiti Hut, we shuck our packs and take the hour-long walk to Korokoro Falls. There’s an otherworldliness about this river valley – even on a clear summer’s day. Surrounded by the gossamer spray of the waterfall, the Tūhoe creation story of the mist maiden Hinepukoho-rangi coupling with Te Maunga, the mountain, makes perfect sense.

Our final day is picturesque. Wandering the lake’s edge, we climb over the Pukehou Ridge and down through the forest, past the kiwi enclosure, eventually arriving at Hopuruahine Landing. We take off our boots and sprawl out on the slipway to wait for the water taxi. My pack is light but my heart is full.

– Jacqui Gibson is a freelance writer living in Wellington

In the neighbourhood

Alternative track: The three day Mangamate Loop Track is a worthy Te Urewera alternative which takes in the Te Whāiti-Nui-a-Toi Canyon, Whirinaki Waterfall, and one of the best podocarp forests in the country.

Since you’re already here: The small but scenic Lake Waikareiti can be reached on an easy 2hr track north east of Waikaremoana.

Just got a weekend? Take the Lake Waikareiti Track, and continue to Sandy Bay Hut, an 18-bunker on the north eastern shore of the lake.

Where to stay: Waikaremoana Holiday Park provides lakefront accommodation between Onepoto and Hopuruahine Landing.

Where to stock up: The closest supermarket is in Wairoa, one hour away.

Walking the Lake Waikaremoana Track

Visit the gem of Tūhoe with a four day walk around Lake Waikaremoana

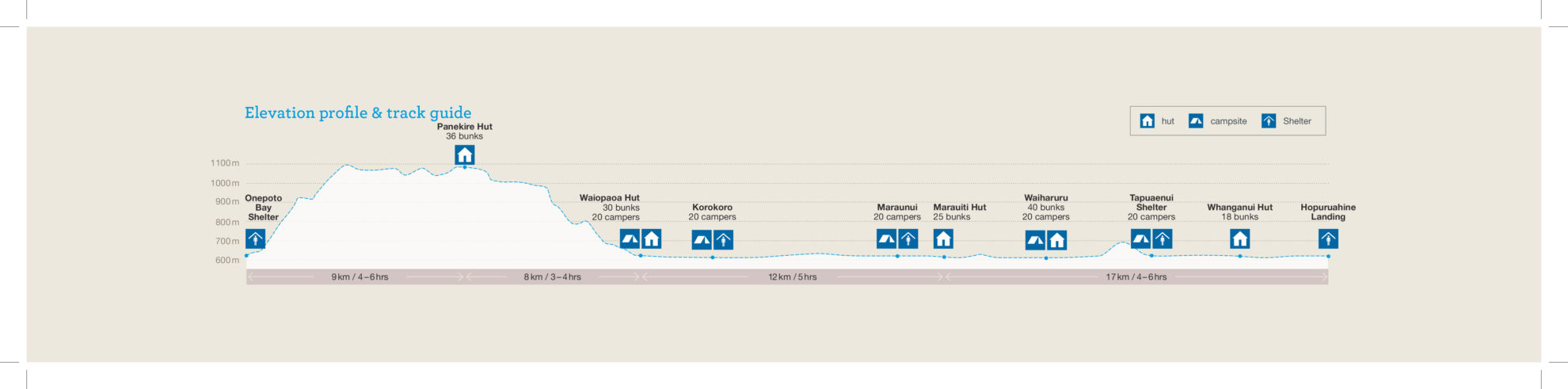

Onepoto to Panekire Hut

9km, 4-6hr

From Onepoto Shelter, the track wastes no time in testing your lungs and legs with a strenuous ascent to Panekire Bluffs. Views over the lake are spectacular, though the exposure is too, and trampers would do well to watch their feet. From here, the track follows an undulating ridgeline to 36 bunk Panekire Hut.

Panekire Hut to Waiopaoa Hut

8km, 3-4hr

The day begins with a gradual descent through mossy podocarp forest. The gradient turns steep at the top of the Panekire descent, and will be a test for the knees. Within a few hours, the lakeside Waiopaoa Hut will be reached.

Waiopaoa Hut to Marauiti Hut

12km, 5hr

Walk up Waiopaoa Stream and cross grassy flats before returning to the lakeshore. At the Korokoro Falls Track junction, an hour-long side trip leads to the 22m falls – a scenic shimmering sheet of water, and one of the North Island’s most idyllic waterfalls. Returning to the track, the route follows the outline of the shore, undulating over headlands and around Te Kotoreotaunoa Point to reach Whakaneke Spur and Marauiti Hut.

Marauiti Hut to Hopuruahine Landing

17km, 4-6hr

The final day is largely flat, with the only notable elevation gain occurring east of Waiharuru Hut, where the track intersects the Puketukutuku Range. It’s a scenic day, and the track sticks by the lake edge for most of the 17km, until finally reaching Hopuruahine Landing, where walkers can water taxi back to the beginning or continue to the road.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us