Writer, historian and translator Ross Calman (Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāi Tahu) previews the trail’s northernmost end and shares how to be culturally respectful as a manuhiri (visitor).

Everywhere on Te Araroa is loaded with significance from a Māori perspective. And for many sections, you’ll be literally walking in the footsteps of tūpuna – the ancestors.

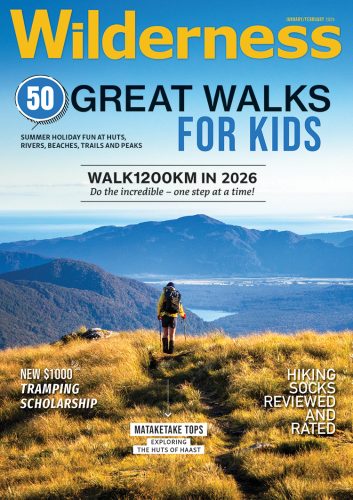

Whether you’re from New Zealand or elsewhere, it’s possible you won’t have spent much time in Te Tai Tokerau Northland; if so, you will likely be blown away by the diversity and the sheer beauty of the trail’s Northland section.

For many walkers the trail starts at Cape Rēinga. It’s a place that features in the collective New Zealand consciousness as being the northern end of the country (although of course North Cape to the east is slightly further north), despite most of us maybe visiting it only one or twice – maybe never – in our lives due to its remoteness. Of course, it marks the starting point (and for northbound walkers the finishing point) of the whole enterprise.

Te Araroa had been on my radar for a number of years and now here I was in a minivan heading north and about to embark on what, exactly? The Unknown. Leaving my wife and work behind, carrying all my gear on my back for close to two months. How would my 52-year-old body cope?

Dave, from Hone Heke Lodge, the minivan driver, had told me it was usually a midlife crisis that motivated people my age to walk the trail. Maybe he was right.

Also making his way to the cape with me was Theo, a young Parisian who had a huge backpack and an ammunition box strapped to his thigh – ‘best purchase I ever made,’ he told me. He was talking a very big game – 50km days.

We were heading for Cape Rēinga but unfortunately the track from the lighthouse around to Twilight Beach was closed. The cause was said to be a combination of feral dogs and politics.

We were still heading to the cape though, so that we could soak in the place’s ambience and pay our respects before hitting the trail, which then began 15km back down SH1 at Te Paki Stream. I’d been to Cape Rēinga once before, in 1985. Then, much of the highway north of Kaitāia was gravel road.

Up that narrow spine of land to the cape, the landscape and vegetation starts to feel like tropical Polynesia.

Then, at the cape is the power of the collision between Te Moana-tāpokopoko-a-Tāwhaki, the Tasman Sea to the west, and Te Moananui-a-Kiwa, the Pacific Ocean to the east. The winds from both quarters also seem to be locked in an endless tussle for supremacy. To the east is Spirits Bay, Te Kapowairua.

In Māori tradition, Cape Rēinga, or Te Rēinga as it’s also known, is the Leaping Place of the Spirits, Te Rerenga Wairua – a notion that is shared with other Polynesian cultures. It marks the boundary between life and death.

Beyond lies Rarohenga, the Polynesian Underworld. Despite its name and location, Rarohenga is no dark and shady place. Rather it was thought to be a place of sunlight, with lakes and forests, with people tending to their kūmara gardens.

An ancient pōhutukawa tree at Te Rēinga provides a ladder for spirits to descend into the Underworld through the swirling waters off the cape. In former times, the entrances to kūmara pits in the Far North were oriented to the north so that spirits would not enter them by mistake making the contents tapu (sacred) and therefore inedible.

You can feel the power of the place. It hit me smack on the chest and my eyes welled up with tears within minutes of arriving. One day, I thought, my own wairua would return and leap off this point and travel into the Underworld.

I walked to the lighthouse, taking obligatory selfies before turning around and walking back towards the van. I would not be leaping today.

Where the track branched off towards Twilight Beach I stopped and gazed mournfully past the ‘Track Closed’ sign down at the pure white sands of the beach and the dune headlands beyond. It will have to keep for another day, I thought.

I said goodbye to Theo. He was going to walk down SH1 rather than get a lift to Te Paki Stream. He wanted to cover the ground on foot, and all the material I had read emphasised the importance of ‘walking your own walk’ – don’t worry what others are up to; in my case, trying to keep up with younger, fitter people could lead to injuries. I didn’t fancy a hot road walk and opted to be dropped at the stream. So we left Theo at the car park shouldering his humongous pack. I didn’t see him again.

Ten minutes later I was at a layby near the end of the road. As Dave drove away it felt like when I was left alone with my baby daughter for the first time. What am I supposed to do now? I hoisted my full pack. It was heavy! If there had been a rubbish bin there, I’d have thrown out some of my heavier food items.

Realising there was nothing else for it, I took off my trail shoes and walked gingerly along the bright orange-coloured streambed in bare feet. It was a Zen experience; taking one step at a time. After an hour and a half of very slow walking, I hit the beach proper – my first trail milestone. Only 2997km to go.

How to be culturally respectful while walking Te Araroa

No matter where you’re from, according to Māori custom you’re going to be a manuhiri (visitor) for the majority – if not all – of your time on Te Araroa. Just like when you visit someone’s house, you need to abide by their rules. There’s not too much to remember, but it’s important stuff:

⇨ Do your bit, pay the Te Araroa registration fee and donation, and camp fees. Often camping areas operate an honesty system where you leave some money in a tin or you transfer funds to a bank account. This is usually a small amount like $10. Just pay it.

⇨ Respect track closures. Follow the trail guidance and keep off private property.

⇨ Leave no trace, whether stopping for meal breaks or for the night. Don’t leave litter, or food scraps. Pack all litter out and leave it in a rubbish bin.

⇨ Use a proper toilet, if possible. If you do have an urgent call of nature, make sure you are well off the trail, away from freshwater and that you bury your waste. Don’t leave toilet paper lying around.

⇨ Don’t sit on or put your dirty shoes and socks on tables or benches that are used for food preparation. Apart from being offensive – not only to Māori – this is also unhygienic.

⇨ Do not enter the grounds or take photographs of marae and urupā (burial grounds) without permission.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us