Home / Articles / Great Walks / Milford Track

A musical whistle breaks the stillness followed by a harsh screech and an answering chord from the trees. Kākā stir as stars still linger in the sky, in the void so far above these steep and dark canyon walls. Weka call from opposite sides of the valley, their obnoxious volume radiating through the clear air and reaching my ears with a welcome pang of familiarity.

It is almost hard to tell when sunrise arrives as the sky is so far out of reach. I step outside onto the crunchy, frosty ground and notice that there is a touch of orange high above. Dawn at last. The honking of paradise shelducks boosts my departure, blaring through darkness in the otherwise frozen and silent world.

This is the second time I’ve been alone on the Milford Track in winter and I love it just as much as that first experience. Despite being known as the ‘finest walk in the world’, this track had never been at the top of my to-do list. Fond of out-of-the-way and other than ordinary tramping locations, I used to think the Milford Track sounded cliché. To my surprise though, I fell madly in love with it – its history, animal and plant communities, and landscape of grandeur. It really is all it’s cracked up to be.

I first set foot on the Milford Track as a shoulder season hut ranger in May 2018 and was hooked from the start. I made a point of walking all the way through the Clinton Valley as soon as the boat dropped me off so that I could spend my first morning in the place I most wanted to experience – Mackinnon Pass. Draping kōtukutuku (tree fuchsia) forests beckoned me onwards and my smile grew with each kilometre. After a night in the cold Mintaro staff quarters, I shot up to the pass to experience a powerful sunrise veiled by a mist of rain with only the company of a kea. I was intrigued as I absorbed the sheer aspect of Mt Balloon. This landscape was stunning but what else would I discover?

I spent the next few days running all over the track and covering as much ground as I could while also keeping the huts tidy and chatting to trampers, many of them young backpackers who had taken the opportunity to do the track ‘on the cheap’ with winter hut prices in force. The busy atmosphere suddenly changed as the weather worsened. Freezing wind and snow down to 300m caused walkers to hurry away, leaving the entire Clinton Valley to me: cloaked in white and magical beyond my expectations. This was anything other than worse weather, this was better by miles. The landscape was transformed and so was my connection to it.

The following days on the track were akin to an artist’s sabbatical. I ran, I wrote, I photographed and I became deeply enchanted with my surroundings. I read about the track’s origins while tucked beside the fires in Mintaro and Clinton huts. Every day was clear and colder than the last. As my senses became fine-tuned, I noticed the smallest things like the growth of ice crystals in the frost hollows, weka tracks in the snow, and kiwi calling at night.

This first experience of the Milford Track is etched deeply in my memory. The Clinton Valley, especially, has become a place of reprieve, connection to my roots, and a landscape in which I feel fully at ease.

I now visit the Milford Track for different reasons to most who tramp it. I spend long days, alone if I can, to further embrace this place that I have found and that I have chosen as home – Fiordland. Adding to my experiential memory, layer by layer, is such a gift. A walk, or a run, on the Milford Track reveals more than is expected, every time.

– Crystal is a Fiordland-based photographer with a profound love for all things wild and wonderful.

Meet the warden: Ross Harraway

Ross Haraway has been a hut ranger at Clinton Hut for 11 years.

Best wildlife encounter: That would be helping the Whio Recovery Team, catching and banding whio (blue ducks) in the Arthur River. One of the most memorable and enjoyable moments was having my family stay at my hut and share ‘my patch’. One day, I took my six-year-old grandson down to the Clinton swimming hole and three whio were perched on a shingle spit. Luke walked quietly up to them and I got a great photo of him pointing to them from two metres away.

What’s something you recommend walkers do: Get going on the track as early as possible in the morning to give yourself plenty of time to stop, look and listen and enjoy everything that Fiordland has to offer.

What’s in tramper’s packs: A guy once arrived at Clinton Hut carrying a paddleboard and a skateboard. He had paddled all the way from Te Anau Downs to Glade Wharf. I questioned his intentions because water craft are not allowed in the Clinton or Arthur rivers because of the didymo risk. He objected vigorously saying he was only carrying it. I gave all his gear a real lathering with detergent and left him to it.

Best time to walk the Milford: I think December and January is the best. The birdlife tends to be more visible, the alpine flowers are blooming and the weather tends to be more settled.

Tips for walking the Milford: There is a lot of great equipment, clothing and food available now which is lightweight. This is important, especially if people are not very fit. Buy the best gear you can afford, or borrow it – it will make the trip more enjoyable. I have seen some terrible clothing – jeans, shoddy quality ponchos, unsuitable footwear – which all added up to people not completing the track or having to be evacuated to safety.

In the neighbourhood

Alternative track: With much of Fiordland National Park still closed, the Gillespie Pass Circuit is a classic track sure to satisfy most trampers.

Since you’re already here: If the weather is fine, tackle the stunning Gertrude Saddle.

Just got a weekend? Spend a night at Milford Sound and take a day walk to one of the track’s highlights: Giant Gate Falls.

Where to stay: Bookend your trip with a night at Te Anau or Milford Sound.

Where to stock up: There are several outdoor gear retailers (and even gear hire) in Te Anau.

Walking the Milford Track

There’s no finer walk than this one-way trail.

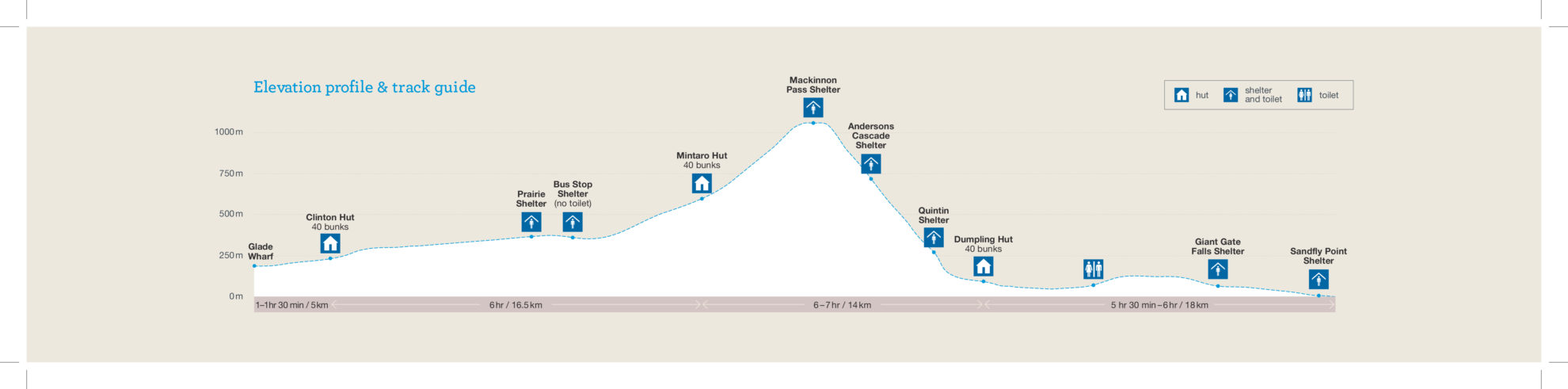

Glade Wharf to Clinton Hut

5km, 1.5hr

The walk begins with a boat cruise across Lake Te Anau to Glade Wharf at the head of the lake. From here, it’s a very leisurely walk through beech forest and alongside the Clinton River to Clinton Hut. You can fill the remaining daylight hours exploring around the hut, where there are some good swimming holes and a short wetland walk.

Clinton Hut to Mintaro Hut

16.5km, 6hr

The track continues up the Clinton Valley, gradually climbing to meet the river’s source at Lake Mintaro. The upper valley is a wild and dramatic place – especially the Clinton Canyon, a defile of rock and precipice 2000m high and split by fissures where waterfalls tumble. The sheer scale of the landscape is mind-boggling. Mintaro Hut sits amongst the forest a short distance from Lake Mintaro and almost directly below Mackinnon Pass.

Mintaro Hut to Dumpling Hut

14km, 6-7hr

Mintaro Hut is the staging point for tackling Mackinnon Pass – the crux of the trip. It’s a steady 550m climb up a steep zig-zag trail to the pass. It’s the most challenging day of the walk. The gorgeous views to Lake Mintaro and the Clinton Canyon encourage a slow pace. From the pass, it’s a descent through an alpine garden alongside the Roaring Burn River.

The track continues to Quintin Lodge and day shelter at the confluence with the Arthur River.

From the shelter, there is a side trip to 580m Sutherland Falls (90min return) – one of New Zealand’s highest waterfalls and a highlight of the track. The track then continues down the Arthur Valley to Dumpling Hut.

Dumpling Hut to Sandfly Point

18km, 5-6hr

From the hut, continue down the Arthur River, passing Mackay Falls and then the classic Giant Gates Falls – which features in many Milford Track photos with trampers standing on the bridge in front of the falls. The track carries on around Lake Ada to reach aptly-named Sandfly Point and the boat to Milford Sound.

The finest walk in the world

The Milford Track has long been known as the ‘finest walk in the world’. It earned its moniker after poet Blanche Baughan visited New Zealand in 1900. She had intended to write poetry that reflected the rough and raw nation, but it was her account of walking the Milford Track, which was published in The Spectator magazine in 1908 under the headline ‘The Finest Walk in the World’ that Boughan has been remembered for.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us