Long before humans could make fire, let alone a lightbulb, nature was already illuminating the dark.

Glowworms can be mesmerising, sparkling like stars or strings of fairy lights. But what are they and how do they glow?

How do glowworms glow?

Bioluminescence is the natural ability of living organisms to produce light through a chemical reaction. It is found in a wide variety of organisms that are not at all closely related, including fungi, plankton, pelagic fish and insects – including glowworms.

The glow is the result of a chemical reaction that involves luciferin, luciferase, adenosine triphosphate and oxygen in the modified malpighian tubules at the tip of the glowworm. The hungrier the glowworm, the stronger the reaction.

What are glowworms, anyway?

In Māori mythology, the glowworm, moko-huruhuru or hine huruhuru, was the only form of light known when Papatūānuku brought life into the world – just a feeble glow. Later they were called titiwai, referring to lights reflected in water. They are generally associated with water and live deep in the bush along sheltered, shady stream banks, or in caves carved by water. The moisture prevents them from desiccation and with water comes food, which they lure into sticky threads with their soft blue-green glow.

Glowworms are carnivorous larvae – but of what?

The answer to that was not known until the late nineteenth century, when G.V. Hudson, an amateur entomologist and postclerk by profession, collected a few from Wellington Botanic Garden and reared them to adulthood. After the larvae went through a pupal stage, small gnats (diptera; true flies) emerged. The adults are no bigger than mosquitoes and quite difficult to spot.

Hudson had to repeat his experiment to convince the professionals, but here we go – they belong to the family of Keroplatidae, which, together with closely related families, belong to the fungus gnats. Hudson gave the specimens to Australian entomologist Frederick Skuse in 1891, who described them as Bolitophila luminosa, which means ‘glowing mushroom lover’ – except these fungus gnats prefer to munch on other small insects, such as midges, small crane flies and caddis flies.

The name was later changed to Arachnocampa luminosa, ‘glowing spider-worm’. Many other Arachnocampa species have been described from Australia.

What about the web?

The larvae not only glow but have evolved a strategy to catch the prey they attract. Glowworms dangle up to 70 threads of silk covered in droplets of sticky mucus, called snares. In a sheltered cave, snares can reach up to 30 to 40cm in length; those built by forest-living specimens reach a maximum length of just 5cm.

Around the larvae is a tube made of the same silk, in which they can move back and forth. When they are disturbed, they shut off the light and retreat through this tube, ideally into a crevice to hide. But if they sense noise or vibrations, they will shine even brighter, and when prey becomes entangled in a snare the larva pulls it up and devours the snare and prey together.

Are they rare?

Glowworms are found only in New Zealand and Australia. While Australia is home to eight known species, it can be tricky to find them there. New Zealand glowworms are widespread in the bush and in caves, although notably absent from Canterbury. So far we know of only one species, but scientists from Te Papa, Otago University and Queensland University are investigating the possibility of others.

These creatures thrive in dark, damp environments with high humidity and abundant prey such as midges, where they face relatively few natural predators. Known predators are spiders and harvestmen or ‘daddy longlegs’. Sometimes the tables turn and a clumsy harvestman becomes ensnared and falls victim to the glowworm instead. Their greatest threat is habitat destruction by humans, such as through land development, pollution and careless cave exploration.

Glowworm caves are among New Zealand’s most popular ecotourism attractions. Because titiwai rely so heavily on stable cave ecosystems, questions are being raised about how climate change – and its impact on humidity, temperature and insect populations – might affect glowworm numbers in the future.

Some places where you can see glowworms for free

→ Waipū Caves (Northland)

→ Cascade Falls (Rotorua)

→ Glow Worm Tunnel (Coromandel)

→ Pukekura Park (New Plymouth)

→ Pohangina Valley (Manawatu-Whanganui)

→ Central Park (Wellington)

→ Hokitika Glowworm Dell (West Coast)

→ Trotters Gorge (Otago)

→ McLean Falls (Catlins)

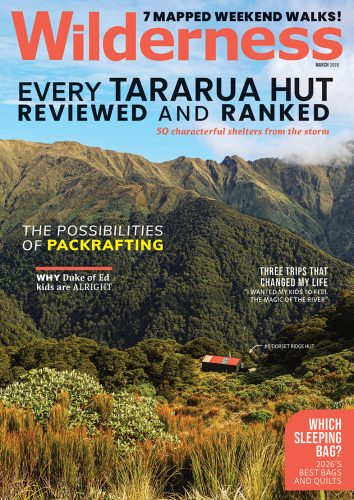

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us