The story of the great Australian mountaineer Freda du Faur, the first woman to climb Aoraki / Mt Cook. By Harry Broad

They climbed to the summits of New Zealand mountains dressed in jackets, ties and knickerbockers. And with no crampons.

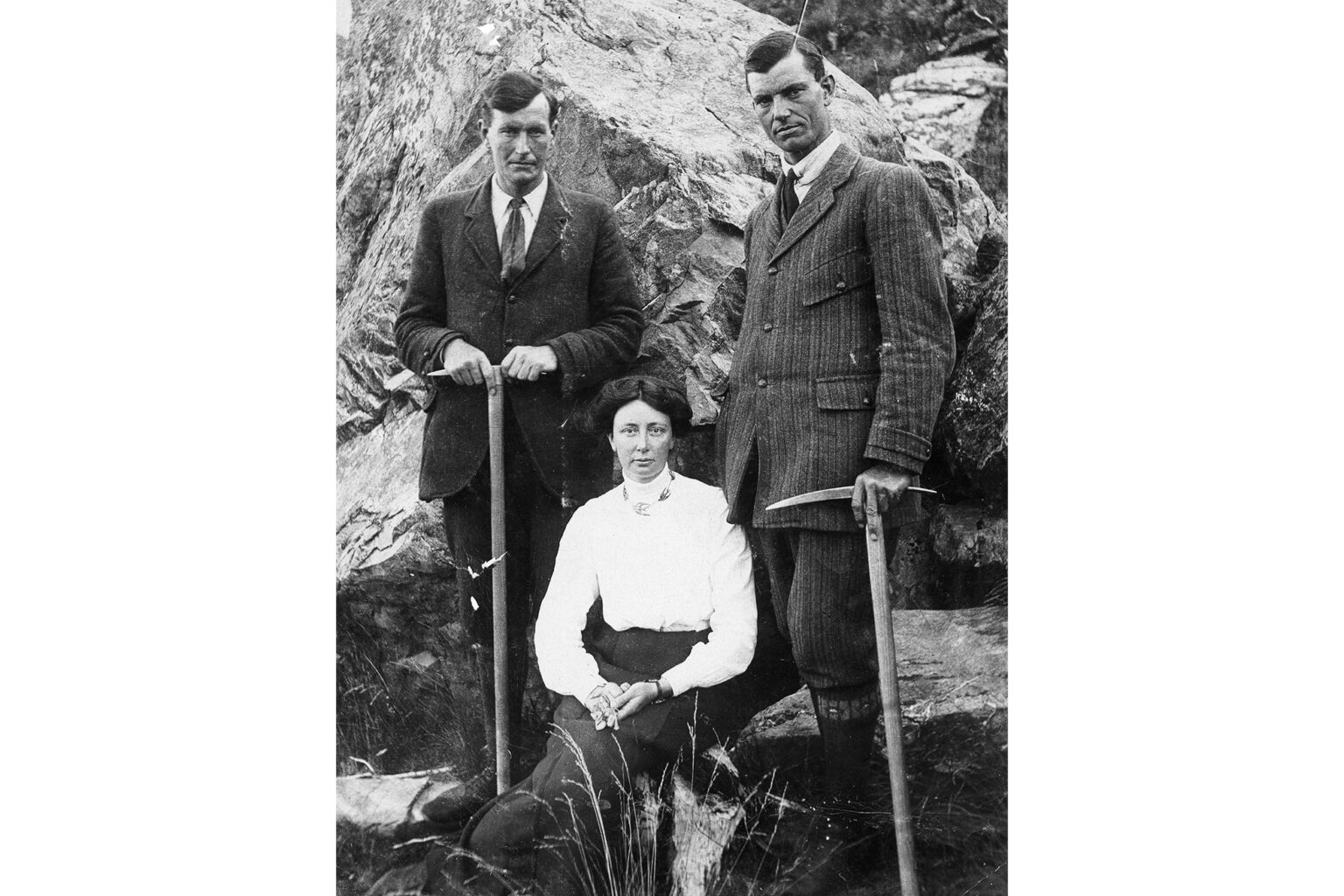

During an intense three years from 1910–13, Freda du Faur with Peter and Alexander (Alec) Graham climbed most of the highest peaks in the Southern Alps, after which du Faur never climbed again.

At 29, du Faur was the first woman to climb Aoraki / Mt Cook. Peter (32) and Alec (29) were her guides. The weather around Aoraki is rarely in a good temper, but on December 4, 1910, it was perfect.

Following that triumph came a grand traverse of Aoraki’s three peaks with Peter Graham and David (Darby) Thomson. Du Faur was the first to climb Mt Dampier, shot up Tasman and Sefton (she was the first to traverse it) and a host of other peaks, one of which was later named after her.

“All the primitive emotions are ours – hunger, thirst, heat and cold, triumph and fear – as yard by yard we win our way to stand as conquerors and survey our realm,” Du Faur wrote in her autobiography, The Conquest of Mt Cook. “Spirit, imagination, name it what you will, it steals into the heart on the lonely silent summits and will not be denied.”

She acknowledged her climbing companions, especially Peter, writing, “No woman ever had two more kind, considerate and trusty companions than the Graham brothers.”

Peter wrote: “In those early years at the Hermitage it was rather rare to meet a woman travelling without any kind of companion, and if one did so she was usually looked on as an eccentric. I usually found after talking to such women on excursions that they had travelled extensively and could give such descriptions of their travels that to act as a guide to them was a privilege.”

The Graham brothers had integrity and also a sense of humour. Over her knickerbockers and puttees Du Faur wore a skirt, which Peter called ‘a mere frill’. On one occasion, when looking to see where Du Faur was and finding her right behind him, he chuckled, “I didn’t know I was taking out a blessed cat.” To begin with, Alec checked on her regularly until Peter cautioned that he “would catch it hot” if he kept doing this.

The trio formed a relationship based on mutual respect and a love of mountain tops. Du Faur was not concerned with convention and insisted they should sleep together when in tents high in the mountains for sheer warmth. Other women at the Hermitage were scandalised, and one pleaded with her not to lose her reputation for the “small matter of a mountain”. Remember, this is 1910; Canterbury Mountaineering Club didn’t admit women until the 1970s.

At 157cm and weighing just 50kg, Du Faur was diminutive but had an innate strength. She could do 18-hour days and never let herself be ‘hauled up’ on the ropes.

Her fascination with mountains began in 1906 when she saw photos of the Southern Alps at the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch. “From the moment my eyes rested on the snowclad alps I worshipped their beauty and was filled with a passionate longing to touch those shining snows and climb to their heights of silence and solitude and feel myself one with the mighty forces around me. Even the train wheels hissed ‘mountain bound, mountain bound’,” she wrote in her autobiography.

Du Faur had heard of Peter Graham by reputation and sought him out. He tested her ability on a 10-hour climb of Mt Wakefield, which she passed with flying colours. She wrote that she felt “for the first time that wonderful thrill of happiness and triumph which repays the mountaineer in one moment for hours of toil and hardship. I returned to the hotel fully convinced that earth held no greater joy than to be a mountaineer.”

For the next four years Du Faur travelled from her home in Sydney for New Zealand’s climbing season and monopolised the Graham brothers. Climbers and friends they were, but formalities were always observed.

Her mountaineering feats attracted interest and praise here (as well as criticism from some male climbers), but in Australia following her Aoraki climb, there was just a short paragraph in the Sydney paper.

She left at Easter 1913 for the last time, sure that she would never see “the star-lit heights and winding valleys again”. “Someday, if my dreams come true, I hope to tackle some of the giants of the Himalayas and I ask no better fate than to be led up them by one of my New Zealand guides,” Du Faur said.

To maintain fitness in Sydney Du Faur joined the Dupain Institute and there met Muriel Cadogan, one of the instructors. The pair formed a close relationship and emigrated to London in January 1914.

After the death of Cadogan in 1929, Du Faur returned to Sydney where she took her own life in 1935. She was 52.

She lay in an unmarked grave for over 70 years until Ashley Gaulter, a New Zealand farmer who had read about her, erected a greywacke headstone as a tribute to this woman who had graced the Southern Alps with her presence.

Challenging conditions

The account of the climb of Mt Sefton gives some idea of the incredible challenges to be overcome.

After a 2am start, sunrise found them threading their way through a “maze of great blocks and pinnacles of ice”. Progress was slow and was made even more so by a sheer wall of ice six metres high. Peter roped and belayed, then stood on a snow bridge across a schrund (a crevasse between the moving and the stagnant ice) that dropped into darkness to cut yet another huge step-up. He balanced in this to cut ever higher over a bulge in the slippery ice wall.

Du Faur followed with difficulty but refused help. When they reached the east side the weather began to turn, and by the time they were facing the worst of the climb on the rotten ridge leading to the north-east arete (a sharp mountain ridge), gusts of wind were blasting up the Copland Valley. Each step required painstaking care. The ridge was 60cm wide at most, with a sheer drop on either side.

Ninety metres of climbing like this brought them “numb and stiff” onto the Sefton rocks. They gingerly scaled the north-east arete across rotten shale. If one of them had fallen it would have been impossible not to drag the other two down as well. They got to within 45m of the summit where the rocks were overhung by icicles in an unbroken fringe.

“What followed was an exciting game of hide and seek with our lives for the forfeit,” wrote Du Faur. Guide Darby Thompson managed to cut steps below the icicles and as they reached the steep arete to the highest peak the wind was so strong that Du Faur was forced to crawl on hands and knees. At the summit they took four hasty photos before beginning their descent.

The trip down was equally hard and after 19 hours they eventually reached the Copland Valley and camped at Douglas Rock Bivouac, where they were forced to stay two nights because the river was in flood. They crossed Copland Pass to Hooker Hut in near-blizzard conditions, and after a quick meal continued to the Hermitage.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us