The kakaruai and the toutouwai may be small but they are skilled jumpers. These beloved songbirds can also count, and recognise people.

Kiwi Olympic gold medal high jumper Hamish Kerr needs to watch out. The kakaruai (South Island robin) and toutouwai (North Island robin) may be small but they can jump big time. Despite being only 18cm tall and weighing 35g, they can jump higher than their own height from a standing start and about twice as far.

And although neither species has won Forest and Bird’s annual Bird of the Year poll, they are undoubtedly among our most beloved bush birds. These sparrow-sized songbirds have a distinct upright stance, a large rounded head and big eyes, long ‘toothpick’ legs and a short, bristled dagger bill.

The male kakaruai has a dark grey-black head and upper body, brownish-black flight feathers and tail, and a white to yellowish-white lower breast and belly. The female is lighter grey with a less extensive pale lower breast and belly area.

The male toutouwai has a grey-blackish head with pale streaking and a pale grey-white patch over its lower breast and belly. The female is the same grey-blackish colour with pale streaking but has a less clearly demarcated lower breast and belly area.

All adult robins also have a small white patch of feathers just above their bill, which they can enlarge to signal caution.

You’re most likely to encounter a robin along forest tracks in the South Island backcountry or the central North Island, or where colonies have been established on pest-free islands such as Tiritiri Matangi and fenced mainland ecosanctuaries, such as Zealandia.

They can be quite bold, approaching closely at sites where people frequently walk through their territories. They will follow trampers, looking for insects the walkers disturb. If you’re lucky, a curious young robin might jump onto your boot and tug at the laces.

Shaun Barnett recounts a remarkable story in A Wild Life. After sleeping outdoors in a beech forest, he woke to find a South Island robin bouncing on his chest. The bird then settled in his hair and tugged at his thinning locks.

However, although robins are reputed to be friendly, researchers have found the birds can be shy in the presence of introduced predators. That’s not such a surprise, since they have an average lifespan of four to five years but may survive up to 16 years where there is intensive predator control.

Being perch-and-pounce predators, robins wait on low branches, scanning the ground before swooping onto their prey. When they land they often flick their wings or tail, or tremble a foot, seemingly to disturb any small insects. In autumn and winter they eat small forest fruits and even the bioluminescent lemon honeycap mushroom.

Amazingly, researchers have found that robins can count food items, and can even recognise different humans. A 2022 study by Rachael Shaw and Annette Harvey found that long-term memory enables North Island robins to remember learned behaviours for up to 22 months, which is about a quarter of their average life span.

They also rank among New Zealand’s most talented songsters. For their size, males sing a surprisingly loud song, proclaiming their territory in a melodic series of repeated pwee-pwee-pwee or tink-tink-tink whistles and chirps that can last for minutes.

A study by Rod Hay recognised over 100 discrete sound elements in their songs. Other researchers have found that both parent birds sing briefly when carrying food to their young, and many adult males serenade their mate with a brief refrain before feeding her while she is sitting on the nest.

The female builds the bulky nest with twigs, bark, grass and leaves, including a woven cup held together by spider’s webs and lined with the small scales of tree ferns, moss, fine grass, feathers and – very rarely – human hair!

Michael Szabo is the author of Native Birds of Aotearoa and the editor of Birds New Zealand magazine.

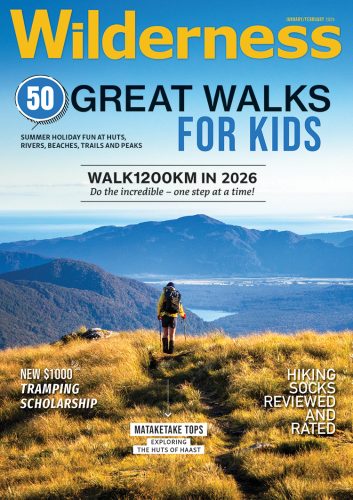

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us