Maps inspire me. I have a particular fondness for topographical sheets produced by Land Information New Zealand: the simple colours, the shading that lends form to ridges and gullies, the symbols and the hatching. A sheet like my old M30 Matakitaki is filled, margin to margin, almost entirely with mountains that offer countless possibilities for trips.

At the 1:50,000 scale, these maps provide a lot of information for trampers: thick bands of orange contours warn of bluffs, shades of green show subalpine scrub, striations represent gorges.

Maps are, of course, a simplistic representation of the landscape and the scale is not so detailed as to rob us of mystery. Planning a trip from the map alone, guessing at the challenges and rewards that untracked terrain might offer, surely counts as one of tramping’s most satisfying experiences.

It had been a couple of decades since I’d been in the Matakitaki Valley, part of a large chunk of country added to Nelson Lakes National Park in 1983. It’s accessible from Murchison, with a track up the main valley and various routes onto the ranges above. On one side it’s flanked by the Nardoo tops and Emily Peaks; on the other is the Ella Range.

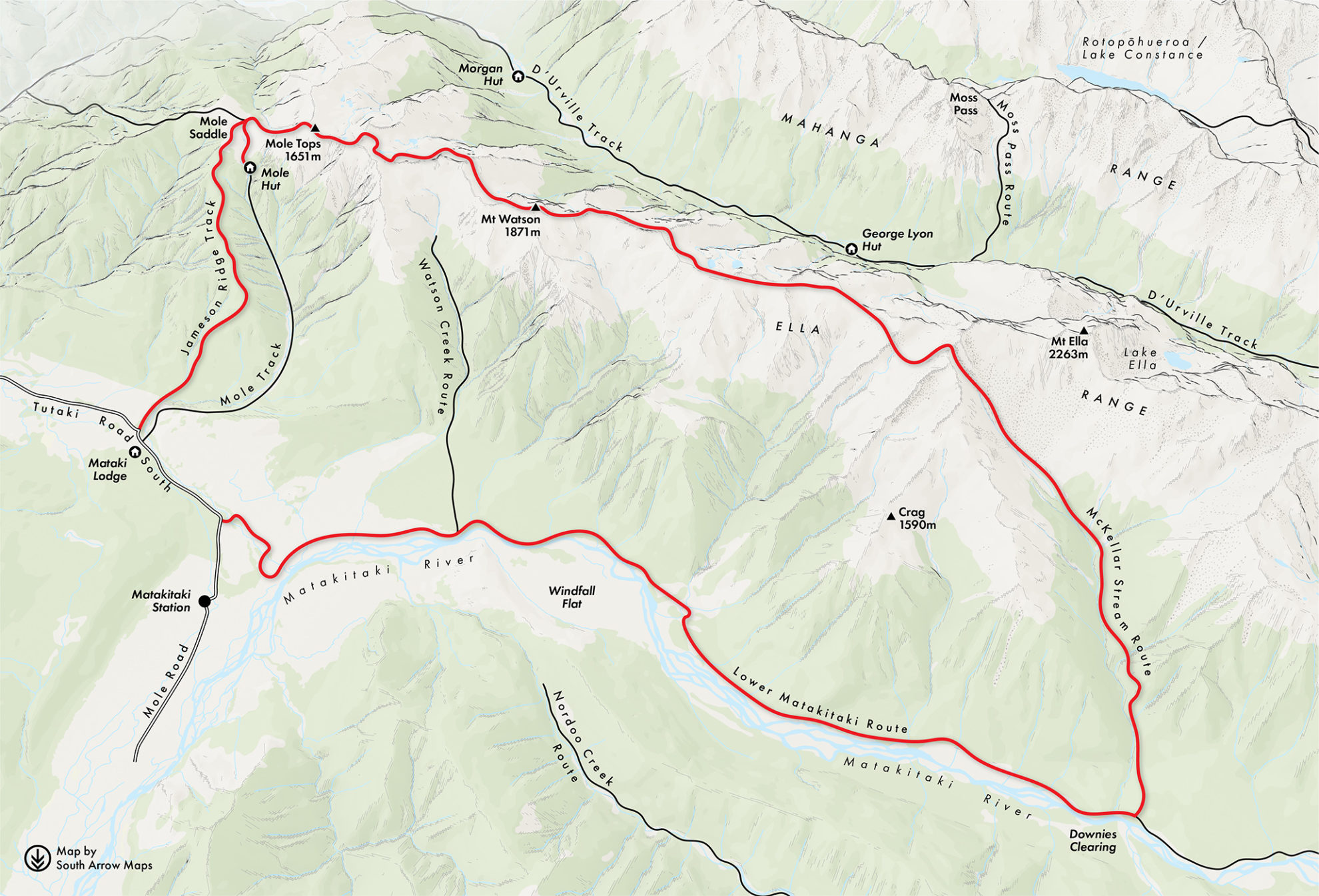

Peter Laurenson and I had toyed with a trip to the Nardoo tops, but heavy rain was forecast for our first day. The map offered a solution: we could tramp up the Jameson Ridge Track to Mole Hut and shelter there until it cleared. Then we’d be ideally placed to traverse along the Ella Range. Contours suggested bluffs and narrow ridge tops, but nothing too formidable. And the map showed those most alluring symbols: a myriad of small, blue shapes representing tarns. We’d take a tent and pick the best basins for camping.

Jameson Ridge Track proved an easy way onto the tops. On an overcast afternoon, carrying five-day packs, we climbed through beech forest – steeply at first, but the gradient soon levelled off. The increasingly stunted forest changed to tussocky clearings not long before we reached the bushline. Mole Hut, nestled down valley on a hillside surrounded by gnarled beech trees, looked inviting. The map showed a poled route around Mole Saddle, which we followed, despite suspecting there might be a direct unmarked route (there is).

No matter, we reached the tidy Mole Hut just as the first heavy raindrops began to fall. Peter cooked while I wrote my diary, both smug with the satisfaction of being sheltered from the downpour. I’d been to Mole Hut in 1991 when it was a rustic ruin with hay bales for bedding. Now it was a comfortable, cosy haven.

The MetService forecasters were spot-on and we woke to clearing skies and the fresh air you get after rain. Mole Saddle was farmed in the past. Much of the tussock that now exists replaced areas of beech forest that were presumably burned off.

Above Mole Saddle the views unfolded, with Lake Rotoroa nearby and the more distant mountains of the Victoria Range and Kahurangi to the west. The first of many tarns greeted us on the Mole Tops, arrayed like blue beads on a necklace. An absence of wind made the reflections near perfect.

Across the D’Urville Valley was the Mahanga Range, which seemed to lack many basins and had instead an abundance of scree slopes. Why the difference? It dawned on me that the Ella Range was mainly schist, the rock more common on the western side of Kā Tiritiri o te Moana / Southern Alps.

Although also a sedimentary rock like the greywacke of the more eastern ranges, schist is more resistant to weathering and erosion. That’s what the map couldn’t show us: how schist shapes the landforms of the Ella Range, and how that in turn affected the nature of our tramping. We found ourselves weaving through schist fins and fissures, over boulder fields and across slopes with unexpected ledges and hidden gullies. At times it was like solving a puzzle. Where would this route go? Left or right? When should we drop off the ridge to try the flatter terrain below?

It soon became obvious that the fastest route was linking basins: choosing the side with the easiest contours, picking a route over the spiny ridge crest and contouring around, past tarn after tarn.

And what tarns: deep and blue, often surrounded by artfully placed rocks or delicate alpine wetlands. We were there in late summer and most alpine plants had finished flowering, but tardy gentians, prickly spaniards, slender willowherbs and the last hardy edelweiss remained.

Much of the vegetated terrain consisted of carpet grass (Chionochloa australis). Because it grows downhill, this short-leafed tussock can be treacherous when wet or on steep terrain but otherwise makes for idyllic tramping underfoot. In places whorls of ground-hugging white cushion mountain daisy (Celmisia sessiliflora) grew like floral wallpaper; elsewhere delicate red tendrils of Drosera sundew, festooned with fly-catching sticky droplets, protruded from alpine bogs. And snowberries! At times we feasted on these white fruits, succulent and tasty after the recent rain. We saw bobbing pipits and a lone wheeling harrier but no kea, which saddened me. Surely they should be here, eating these abundant berries?

Threading through one rocky gap into yet another basin, Peter suggested we scramble up a nearby peak. Summits always appeal to him, and he strode off purposefully, shaming me into following him. As always, the view was worth it.

Afternoon cloud shimmied in, but it wasn’t threatening, and past Mt Watson we joined gullies, sidled beneath bluffs and avoided sharp schisty serrations until we were in another mellow basin (near Pt1916m). This one had two substantial tarns, almost alpine lakes, with smaller ones above. While the potential for swimming and photography of the larger lower tarns tempted me, Peter suggested we stay high where we could easily reach the nearby ridge for sunset and sunrise. So we set the tent on a convenient knoll not five metres from water. As my low tarns sunk into shade, we remained in the sun, proving Peter’s choice as the better one.

Off-track travel encourages this constant dialogue – about the route, the best place to pitch the tent, the opportunities for photography. Making it up as we went along, we used the map where it could guide us, and our experience when it couldn’t.

I cooked, and just on dusk an armada of low cumulus sailed in from the north, surrounding Mt Hopeless and the edge of the Mahanga Range but leaving the Ella Range clear. It was sublime.

While the following day was sunny, a latent coolness kept away the sapping heat that can come with summer tramping. As we progressed south along the range, the mountains got higher, edging towards 2000m, and the slopes were correspondingly steeper. Alpine grasshoppers jumped about, their long, powerful legs catapulting them hundreds of times their own height into the air, only to land at some random place beyond. We watched one flop into a tarn. It deftly swam to the edge and climbed out.

Taking to the ridge again, we were soon among a serration of schist fins and had to squeeze through gaps, clamber over large boulders and avoid a nasty drop to the east. As the ridge grew narrower, we realised we’d have to either backtrack or find an exit route down a gully. Peter found a likely gully and we eased ourselves down, taking care not to slip.

There was another divine tarn in the basin below. Beyond, we climbed a spur, where we found an unexpected but clearly defined trail marked by regular droppings. Ungulates of some sort. As we lunched on top, I spotted movement in the valley below.

“Look, deer!” I exclaimed to Peter, counting four, then five, then as many as a dozen, moving in a herd. They must have crossed the pass just before us because their fresh hoof marks had gouged a clear route down the far side.

By now we were nearing the most rugged part of the range, Mt Ella (2263m). Navigation became critical, and while our map-reading had so far been impeccable, we now made a mistake. We were aiming for a high crossing just west of Pt2105m, which would lead us into McKellar Stream. Assuming there were two possibilities, we chose the wrong col and found ourselves looking between bluffs, unsure if we could pick a route to the steep scree gully below. We sat among the largest flock of vegetable sheep I’ve seen while examining the map and considering what to do.

Discretion, Peter suggested, might be the better part of valour – and it was. We backtracked, avoiding what would have been difficult travel with packs. Having climbed to the correct col, we could now look down into McKellar Stream. Below was a curious horseshoe-shaped ring of beech forest surrounding a tussock flat that looked good for camping. But first we had to negotiate a huge 700m scree descent.

Maps show scree slopes with black dots but offer no detail about the quality of the scree. Would it be delightfully loose, small-sized scree that can be run down? No. Instead we had a reasonably gruelling slog down schist blocks of varying size and quality, crossing a rock hummock that seemed like it had been compressed into shape by the weight of the slowly moving slope above.

Halfway down we sidled east into another gully to avoid a small gorge. Dividing the two gullies was a rib that ended in bluffs: another terrain trap that the map only hinted at.

We’d been on the trot for eight hours when we thankfully reached flatter terrain. A recent flood had washed through the area, battering tussock and re-routing the McKellar streambed. We pitched the tent on one of the new gravel flats that had been created.

Lazing while the billy boiled, my back against a convenient boulder, I had that happy contentment that only comes when you are agreeably tired from a good day’s tramping, satisfied from covering new terrain and meeting its challenges. The last of the evening light played across the steep jagged slopes of Mt Ella above.

The map showed a dotted line indicating the McKellar Stream route, our exit off the Ella Range into the Matakitaki Valley. Again, the map gives away nothing about the route’s condition.

“Best we can hope for,” I said to Peter, “is that it’s marked, but I doubt it’s been maintained for years.”

So we were pleasantly surprised to find the trail well marked and reasonably well defined – at first. McKellar Stream starts as a series of cascades among mossy trees. But lower down there was windfall, the hum of wasps, and the challenge of staying on track. As an old hand at this sort of travel, I made a reasonable fist of it, leading and guessing, calling back corrections to Peter when I went astray. By a mixture of luck and skill we reached the main Matakitaki Valley track in reasonable time, unstung and not too grazed from the bush-bashing.

“A simple plod down-valley on a good wide track,” I promised Peter. Famous last words. Mostly it was, but the recent storm had eaten away the track edge, and in a few places had obliterated it. Bush-lawyer snagged and bushes slapped us before we could pitch the tent at what was known as Matakitaki Base Hut. The hut that existed here last time I visited was long gone. Weka screeched, sandflies drove us insane, the river burbled, and as dusk settled over the valley the forecasted cloud arrived. Before dawn the drizzle began, and we departed early to walk back to the car.

In between bouts of rain, we’d enjoyed two extraordinary days traversing the Ella Range in good weather as promised by the MetService forecasters. Their map reading had proved as important as our own.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us