In a tūī versus korimako head-to-head, which bird comes out on top?

Two of our best-known endemic songsters, the tūī and the korimako bellbird, may not sell out stadiums like Taylor Swift, but they sing in sublime ways that she can’t.

That’s because all songbird species have a ‘voice box’ or syrinx at the junction of their two bronchial tubes, which vibrate independently to allow a personal duet.

Not all birds use this box, but the tūī and the korimako do so expertly.

A tūī’s song is a complex mix of flute-like notes, trills and whistles peppered with noisy grunts, gurgles and wheezes. The korimako has a quieter, more fluid song with melodic whistling and chiming notes punctuated with coughs, gurgles and clicks, but, unlike the tūī, no grunts and wheezes.

These birds ‘sing’ early and late in the day to advertise their territories. The sublime songs of both herald the arrival of spring. They also have local song dialects, which is why bellbirds on different islands in the Hauraki Gulf have different songs.

HMS Endeavour naturalist Georg Forster described the korimako’s song, which he heard in Queen Charlotte Sound in 1770, as “almost imitating small bells” – hence bellbird, their English name. Their call in that location is likely to be different now because of the way their song has evolved over time.

Research by Dr Michelle Roper in 2019 found that the syrinx of female bellbirds is smaller than that of a male. This may explain why male bellbirds can sing at higher frequency ranges.

The tūī is the glittering A-lister of the two. It won the inaugural Bird of the Year poll in 2005, something the smaller and less showy bellbird has yet to do.

Their collective nouns are also instructive. ‘An ecstasy of tui’ suggests the decadent life of an avian rock star, while a ‘chime of bellbirds’ seems distinctly clerical.

Visual differences are also striking. The tūī is a shimmering dandy dressed in black satin with glossy green and blue flashes, draped with a white lacy cape and a fluffy white cravat. In contrast, the bellbird looks slightly drab. The olive-green and charcoal-grey male is distinguished by his subtle purple-tinted head. The female is browner with a pale facial stripe and a crown of bluish hue.

Tūī grow to 30cm, korimako to 20cm. In both species, the male is larger than the female. The tūī is also comparatively heavy: males weigh up to 125g, almost four times heavier than male korimako.

Tūī have a notched 8th primary feather on each wing that creates a loud whooshing sound in flight. This can be heard during spectacular display flights, when tūī soar high into the sky before diving steeply. A korimako’s flight is stealthier.

Both birds feed on nectar and are important pollinators. They can twist open the closed flowers of native mistletoe, and when they feed on nectar with their brush-tipped tongue, golden flax pollen and blue tree fuchsia pollen rubs onto them, colouring their crown and face. They also disperse the seeds of native plants that produce small fruits, such as tree fuchsia.

Fruits and nectar are seasonal so tūī and korimako need other food sources. In beech forests, the sugary ‘honeydew’ excreted by scale insects that live on beech trunks provides both birds with year-round sustenance.

So next time you hear one singing, stop and listen to find out if you’re an avid tūī fan or captured by korimako – it’s cheaper than tickets for Taylor Swift..

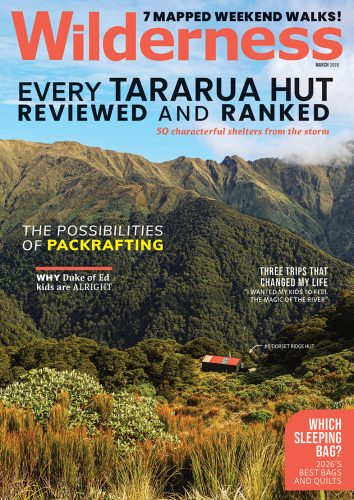

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us