Their itch is a nuisance, but the namu, or sandfly, makes a remarkable contribution to the cleanliness and health of New Zealand’s waterways. By Julia Kasper

The New Zealand sandfly is an iconic insect. But unlike wētā or glow-worms, they are unpopular because of their thirst for blood and the itchy swellings they leave behind on their host’s skin. Their dense swarms can make it nearly impossible to stay longer than a few minutes in places where sandflies are abundant.

Unfortunately, those are often places of breathtaking beauty, like the bush, beaches, lakes and rivers of Fiordland or the West Coast. Arguably, these places are still magnificent simply because humans are less eager to spoil them thanks to their unpleasant guardians – exactly as foretold in Māori mythology.

The New Zealand sandfly (Austrosimulium sp) belongs to the family Simuliidae, known worldwide as the blackfly. The name ‘sandfly’ is used for different groups of flies depending on geographic regions. For example, the sandfly (Phlobotomus) of the family Psychodidae is a strong medical vector of leishmaniasis, a disease caused by a protozoon parasite in the tropics and subtropics of Africa, Asia, the Americas and southern Europe.

Though it doesn’t share the common name, the closely related blackfly in Africa (genus Simulium) can also transmit diseases, such as river blindness.

The genus Austrosimulium occurs only in New Zealand, Tasmania and mainland Australia.

It appears we owe the name ‘sandfly’ to members of James Cook’s voyages to New Zealand, including Cook himself, junior naturalist Georg Forster and botanist Joseph Banks. When they went ashore at Dusky and Doubtful sounds, they found the presence of sandflies utterly disruptive. There are numerous records of the insects in their journals, and the men named them for their abundance on sandy beaches.

Apart from the itchy bites, the namu is not harmful to humans. In fact, most endemic New Zealand sandflies don’t even bite people. Of the 19 species present here, 16 have developed a taste for bird blood – which makes sense because, apart from bats, for millions of years there were no land mammals in Aotearoa.

The other three species like human blood. These three are similar in size (approximately 2–3mm in length), and it is difficult to distinguish them without a microscope. Austrosimulium australense can be found in the North Island; A. ungulatum occurs in the South Island; and A. tillyardianum can be found in both.

Sandflies pierce the skin with their knife-shaped mouthparts and then lick up the blood, rather than sucking like a mosquito. They release an anticoagulant that prevents blood from clotting, and agglutinins that prepare the blood for digestion. This powerful protein cocktail causes a reaction that varies between people. The effect of a bite can be present from a few minutes to several weeks, depending on the severity of the reaction, and secondary infection may occur as a result of scratching.

Only female sandflies feed on blood because they need the proteins to develop eggs. Females that do not take a blood meal can still lay a small number of eggs; if they have had a blood meal they can lay up to 300 eggs, two to three times in their life cycle.

It is not clear what the males feed on, but it is possible that, as with other bloodsucking insects, they use nectar as their energy source and are accidental pollinators of native plants. However, as they are rarely seen, it is believed that they live only long enough to mate. The females copulate just once in a lifetime and store sperm to fertilise each new batch of eggs.

These eggs are laid in running water and cling to mud, rocks or vegetation. They take about 10 days to hatch into small larvae, which attach themselves to vegetation or rocks in flowing water. Before they form cocoons of silk where they develop into adult flies, they filter organic matter for food with a set of fan-like structures. They make a remarkable contribution to keeping New Zealand’s waterways clean and healthy, even if the adults are sometimes quite literally a bloody nuisance!

Dr Julia Kasper is the lead curator of invertebrates at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. She is an entomologist specialising in flies.

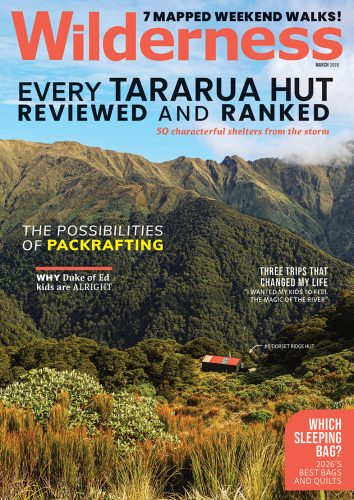

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us