It’s getting dark as we stumble around in the swampy tussock looking for flat, dry spots big enough to pitch two tents. We settle on two sites, shouting distance apart, and drop packs that are loaded to the brim with 10 days’ food.

The tents are set up fast – by torchlight – and Hana, Anna, James and I are soon sitting inside. There are no sandflies so the doors are wide open. As I cook I watch the mist make a slow-motion tumble through the saddle while weka begin their dusk racket and two kea call raucously above. After an early start in the city, a long drive and several hours of walking up Styx Valley, we’ve arrived, and it’s so good to be here.

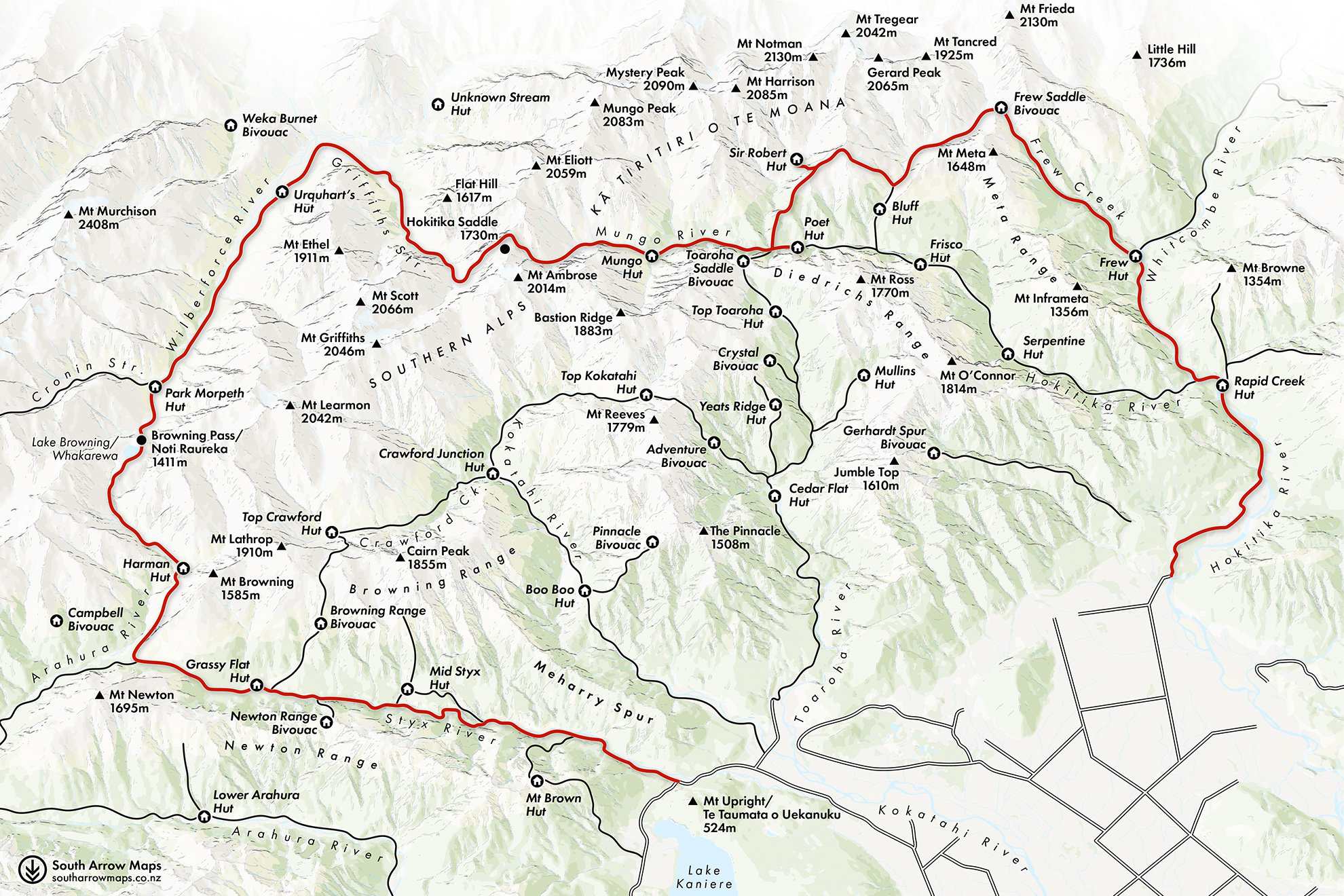

We’ve got nine and a half days to play with. Our 110km route is from Styx Valley to the Whitcombe Valley with two crossings of the Main Divide, via Browning Pass and Hokitika Saddle. We’re looking forward to visiting a few huts for the first time. If there’s a trip goal, it’s to get to Sir Robert Hut, one of the least visited huts in the country.

Sir Robert is high up a rugged alpine stream that drains the Divide. It defines remote: off-track, and a few days are required for a round trip. Bouts of heavy rain are forecast and our plan feels tenuous, but we’ve allowed some flexibility.

It’s close to Easter and the days are getting shorter, so we leave Styx Saddle before dawn and head to Harman Hut along a historic pack track hewn into the valley wall.

Prior to European settlement, Māori used the Browning Pass crossing as a pounamu trade route, but it was later abandoned in favour of less exposed routes. Around the mid-1860s settlers forged a droving track over the pass to supply West Coast gold miners with supplies from Canterbury. In those days the isolated Coast had closer ties with Australian ports than it did with Christchurch. There were calls to develop a road over Browning Pass but this idea was abandoned in favour of Arthur’s Pass, further north. I feel in awe of the pioneers as we cross a swingbridge over the ravine of the Harman River, and again when the pack track peters out into the chaos of a stony riverbed and climbs steep tussock past bluffs on the way to the pass.

The wind is picking up steadily when we reach Whakarewa Lake Browning, cradled in the tussock basin just below the pass.

Browning Pass descends steeply into Canterbury’s Wilberforce Valley, and we make our way carefully down a loose goat track. The lazy switchbacks of the 160-year-old bridle path remain etched into the scree.

The rain starts soon after we reach Park Morpeth Hut and continues heavily into the early hours. Cronin Stream, which was inaudible when we wriggled into our bags, begins to roar and I can hear rocks tumbling.

When we leave the hut next day, it’s in light rain, but we’re unsure if we’ll even be able to cross the Wilberforce. The mountains are lost to a uniform grey that descends to the river. But we agree on a crossing point, link up and wade through the cold, rough water.

An hour and a half downstream we reach Gifford Stream, the only big watercourse between us and Urquharts Hut. The rain has stopped, but it’s cold in the wind and I have my fingers drawn into my sleeves as we trudge upstream alongside the dark, churning water, looking for a place to cross. We can’t see the bottom of the flooded stream and risk being washed into the Wilberforce, so decide to wait. James marks the water’s edge with a cairn and we pitch a tent fly. With four inside we’re soon warm with steam from a brew filling the space. We lunch slowly and fall asleep, huddled between wet packs.

Five hours later the stream has dropped about 30cm. We link up and cross and then continue down the valley with a sense of urgency. Much of the day is gone, and with more rain on the way we want to be in position to cross Hokitika Saddle the next day.

With its dirt floor and canvas bunks, Urquharts Hut has historical charm, but we continue along the flats to Griffiths Stream. Shortly after crossing Griffiths we make a retrospective ‘best decision ever’ when we decide to camp in a sheltered cove. At first it seems a bit early to stop, but darkness comes fast, and rain arrives as I bash in the last tent pegs.

It poured again overnight, the stream swelled and gusts buckled the tent. Before dawn it eases and we leave at first light. For three hours we follow the trackless stream, over, under and between boulders wet from the rain. We wade in the river and fight through a bit of scrub. Like much of the travel on this trip, it is an exercise in micro navigation – finding the safest and most efficient path through a chaotic environment.

The cloud lifted as we reach the base of the spur to Hokitika Saddle. Higher up, we know it will be cold and exposed, so stop for an early lunch so that we are well fuelled for the 700m climb.

From a rocky spur on the climb to the saddle the névé of the Griffiths Glacier can be seen below the cloud covering the Divide. My eyes trace the stream, down past the toe of our route and east from where we’ve come, where the weather’s clearer.

About a third of the way up, the spur steepens and we’re into scrambling mode, tugging on snowgrass and rock ribs. For a short section the exposure is intense as we negotiate a large block on a narrowing in the spur. Then the cloud becomes a squall and the wind picks up, briefly blowing in hail and sleet. We climb through moraine, hoping we’ll have visibility for an unfamiliar descent.

There’s a biting wind chill as we sidle along the rock-strewn crown of the Divide. We’re aiming for a grid reference that I’d earlier marked on my phone map in case of a moment like this when you don’t want to linger. We find the top of a huge scree slope and with long strides descend hundreds of metres into the upper Mungo Valley. It’s more sheltered, but there’s still a couple of boulder-hopping hours to Mungo Hut, so we refuel again.

“We seem to spend a lot of time in overtrousers,” I comment. We’ve had just the briefest flicker of sunlight all day, and I’m enjoying the hot tea in my hands and the steam on my face.

“Yeah, I guess it’s what you sign up for when you tramp on the Coast,” came a response. “If we insisted on fine weather, we’d never get anything done!”

New Zealand’s fickle weather means it’s highly likely there’ll be bad weather on a long trip. So, it’s important to be prepared, to know when to move and when to stay put and to have planned escape routes. For this trip we added a buffer of two half days as well as one actual rest day. A day off allows for recovery or bad weather, but also gives you time to absorb where you are.

An InReach message from our trip contact has confirmed the forecast: heavy rain and severe gale winds about the Divide, easing to showers in the morning.

The route is down Mungo River and up Homeward Ridge before dropping into Sir Robert Creek. River travel is required and a couple of detours into the bush to avoid bluffs and cataracts. Thunder and lightning wake us and the rain is still falling. We can hear the river’s roaring 100m below. We’re not going anywhere.

So, we relax and enjoy the warmth of the fire. In the afternoon it clears and I sit in the sunshine outside the hut listening to bellbirds and watching a large weka graze the tussock. We’d been here two years ago, arriving in the dark and leaving at dawn. It’s good now to soak it up.

In the morning we leave by torchlight. Rain has returned overnight but it’s not heavy. The Park River is fordable and the Mungo doesn’t look too bad. Progress is slow as we cautiously make our way downriver, boulder hopping and wading in its edge. It’s an awe-inspiring place to be, and we feel tiny beside the roaring river and bush-clad slopes soaring into the rain-flecked mist.

A strand of cruise tape hints us onto a rough track and we climb high above the river, cutting in and out of steep gullies. We embrace the wet as we straddle stream boulders, water running up our sleeves as we climb. The hours fly by as we focus on the route, cautious of slipping down a bank or falling in the river.

When we finally reach the bridge below Homeward Ridge, it’s too late and too unpleasant up high to continue to the hut. There’s a dusting of snow along the canopy just below the bushline. We detour to Poet Hut – a short distance – for a late lunch and to dry our clothes, confident that tomorrow will be a fine day.

The moon glows in the dawn sky and frost crunches underfoot as we leave Poet. Like the river detours yesterday, the route up Homeward Ridge has been marked and recut by Permolat volunteers. This was once a key cullers’ route to Sir Robert and the tops, but it was abandoned by DOC. Permolat’s work has maintained, or reopened, many tracks in Central Westland, making trips like ours more feasible.

It’s a steep climb though and as we break out of the trees onto the tops we realise we’ve forgotten what sunshine feels like. High on the ridge we stop to eat, looking up at the snow-capped peaks of the Divide. Mountaineer and photographer John Pascoe was a member of the party that first climbed 11 of these peaks in a day back in 1930, and they’ve seen few ascents since.

From our lunch spot we follow a steep spur into a gully, treading carefully, clutching at plants. When we pop out into a steep tributary of Sir Robert Creek, we know the hut’s less than 200m away. Keen eyes pick out a cairn and a scrap of permolat marker and we find the overgrown track to the hut.

The bright orange four bunker looks as though it sprang like a mushroom out of the surrounding scrub. It’s like entering a time capsule. The hut was built in 1963 by the NZ Forest Service, and it’s retained some of its NZFS-era heritage: a straw broom, a retro can opener on the wall, an old camp oven and magazines from the 60s and 70s. The log book has entries dating back to 1983, revealing the hut’s isolation: an average of two parties per year for the past 40 years. It’s encouraging to see more traffic in recent years, thanks to volunteer work and the profiling of this forgotten mountain sanctuary on the Remote Huts website.

It’s mid-afternoon and two large boulders beside the hut are still in the sunshine, so we scramble up and make a brew, surveying the landscape from our perch and feeling content. It’s is the trip’s seventh day and the main goal is ticked.

For the past two days Hana has had a simmering tooth infection that painkillers can’t quell, so we make the call to bail a day early and exit via Frew Saddle directly to the Whitcombe, instead of via the Diedrichs Range. It’s still a two-day walk, but the weather is fine and the hardest tramping is behind.

On our final night we camp on Frew Saddle, close to another icon of the hut network of this region. Frew Saddle Biv. This biv was built in 1957. It was the first of its type constructed by the NZFS in Central Westland.

Down in the Whitcombe the following day we’re in a different world, humbled by the scale of the river, the giant boulders and the endless bush-clad ridges that enclose the valley. The contrast with the tops and headwaters of previous days provides a powerful conclusion to the trip; and we make our return to the world outside the mountains.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us