People will often say of a place that no two days are the same. In Tongariro National Park, you could almost say no two hours. Mts Tongariro, Ngauruhoe and Ruapehu are to cloud, wind and rain, what a magnet is to metal: an irresistible attraction. One moment you could be covering up from the sun, the next sheltering from the rain or finding your way through a whiteout.

I try to time my trips to the park with the weather, but at this altitude (the three peaks are 1967m, 2287m and 2797m) and with these three magnets, experience has taught me you’re just as well to go because it might not be so bad. Or it might be worse.

My first time on the Northern Circuit, it was worse. I was 14 and on a school trip. Our teachers knew nothing and we students knew less. Our first day included a climb of Ngāuruhoe where we peered into the crater and then ran back down the scree slope. Fourteen-year-old me would call that ‘an unforgettable experience’. Forty-five-year old me cringes in wonder at our collective cultural ignorance. Fortunately, a lot has changed in the intervening years. DOC actively discourages anyone from climbing the peak and during the busiest periods, Māori rangers walk this section of track to remind trampers to stick to the trail. For those willing to listen, these locals provide a valuable cultural element to the walk and a chance to understand why Tongariro is so sacred.

But the fine weather that allowed us up Ngauruhoe turned to gale-force winds that evening. Camped at the base of the Devil’s Staircase, between Ngāuruhoe and Pukekaikiore, we may as well have been camped in a wind tunnel. I was among the few with a proper tent – a K2 model built for the mountains. It protected me and my two classmates but when we poked our heads out in the morning, it was to a scene of carnage. Not a single other tent remained standing. Poles were snapped. Fabric torn. Traumatised students gaped in wonder when they saw our tent, unscathed – had we any idea what horrors they had gone through? Our trip was over before it had begun.

Six years later I was back and once again I carried a tent. I have sharp memories of the cold of the night seeping into my bones as a late-summer snowstorm blanketed everything in white. But it was for a cultural experience of a different kind that I most remember that trip. Oturere Hut was full to the brim and the air thick with accents of every kind. New Zealand was so far off the beaten track in those days I don’t think I had ever spoken to a foreigner before, let alone met one. But the world had come to Oturere Hut and it sparked within me a desire to travel abroad and see the world.

My most recent experience of the track was last winter, alone. I don’t think I’ve ever been so scared in the outdoors as I was when I climbed to Red Crater. The ice was so hard, my crampons barely seemed to scratch the surface. The wind howled and my hands became so cold I struggled to grip my ice axe. Rime ice clung horizontally to the snow poles like daggers pointing back the way I’d come. Turn back, they seemed to scream. I almost did. But somehow I carried on and all of a sudden everything was quiet. A few metres down the slope towards Emerald Lakes and the wind and the cloud disappeared. Blue skies beckoned and in the tranquil Oturere Valley, it seemed impossible that just an hour previously I had been so buffeted by the wind I thought I should retreat.

You walk the Tongariro Northern Circuit on its terms. And as great as the scenery is – and truly, it is remarkable and so utterly unique you will not find anything like it anywhere else – it is also so much more. It is a journey where cultures collide. It is a trial and a test of your endurance. And it is a magnet – drawing me back, time and again.

In the neighbourhood

Alternative track: Ruapehu’s Round the Mountain Track is a 66km loop best tackled over 4-6 days. The northern section incorporates the Northern Circuit, but the majority is spent on the slopes of Ruapehu.

Since you’re already here: Silica Rapids Walk is a 7km loop track which explores the Silica Rapid terraces. The track starts near the Chateau Tongariro and can be completed in 2.5hr.

Just got a weekend? From Whakapapa, take in the Taranaki Falls and Tama lakes on a trip to Waihohonu Hut – the best hut in the park.

Where to stay: National Park Village has options and the Chateau Tongariro is minutes from the start of the track.

Where to stock up: National Park Four Square is the nearest supermarket, and gear hire is available at The Alpine Centre.

Walking the Tongariro Northern Circuit

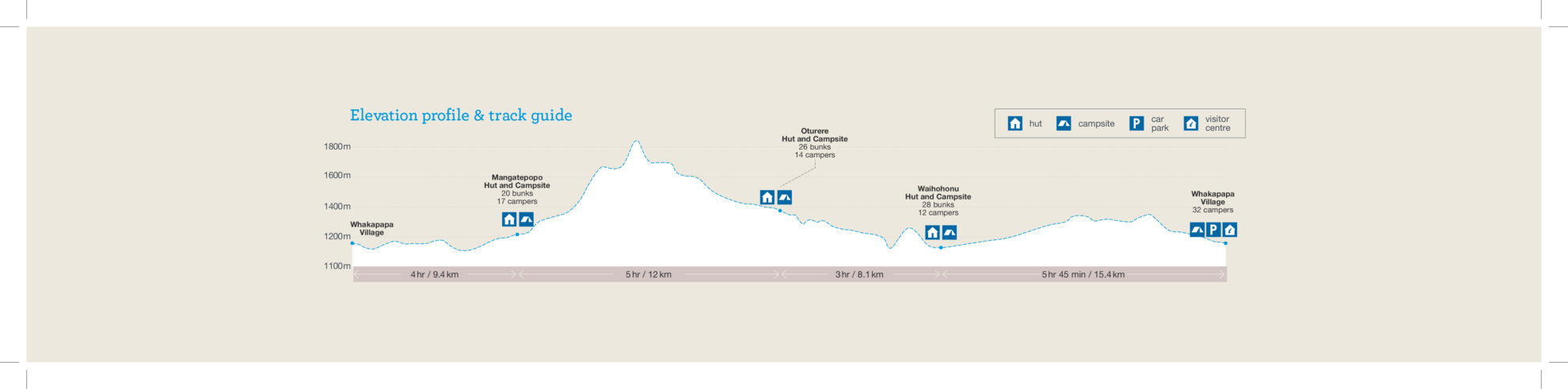

The three-four day Tongariro Northern Circuit is best done in a clockwise direction.

Whakapapa Village to Mangatepopo Hut

8.5km, 3hr

From Whakapapa Village, head north on the heavily eroded Mangatepopo Track. It’s harder work than the distance and time imply: the trail drops into and climbs out of more streams than you can count and, compared to other sections of the track, it’s in poor condition. But towering Ngāuruhoe and smaller Pukekaikiore serve as constant reminders that you are walking in a World Heritage Area. Regardless, you’ll be pleased to reach the hut.

Mangatepopo Hut to Oturere Hut

13km, 4-5hr

Now the fun begins. This section, on the Tongariro Alpine Crossing, is undoubtedly a highlight, though you may wish to rise early to avoid the day-trippers who will be crowding the trail as far as Emerald Lakes.

The boardwalk trail to the Devils Staircase is quickly dispensed with and though the climb to South Crater will get you puffing, you’ll have plenty of time to recover your breath on the flat 1km march across the crater – Mts Ngāuruhoe and Tongariro on either side.

The steep climb to Red Crater brings you to the exposed 1868m highpoint of the walk. The weather here can be extreme at any time of year, but if conditions are good it’s worth pausing here to admire the view of the park’s three major volcanoes.

It’s then all downhill, first to spark-ling Emerald Lakes and then beside Oturere Stream to

Oturere Hut. Oturere Hut to Waihohonu Hut

7.5km, 3hr

The track now swings to the south, around Ngāuruhoe, and is mostly flat and easy walking. Above the treeline for most of the walk, unobstructed views can be had in all directions – particularly good is the view east to the Kaimanawa Mountains. There’s a sting in the tail to this section, though: a steep climb through forest and then one final descent to the hut.

Waihohonu Hut to Whakapapa Village

14.3km, 5hr

Get started early on this section to make the most of three side trips. First up, just 15-minutes from the hut is the historic Old Waihohonu Hut, built by the Tourist Department in 1903-04. It’s a far cry from the luxury of the new hut.

The trail is again mostly flat and passes through a wide-open valley that separates Ngāuruhoe and Mt Ruapehu. It climbs gently to the track junction with the Tama Lakes Track, where a trail leads north to offer a vantage of both Lower Tama (20min return) and Upper Tama (90min return). It’s well worth the detour to see these lakes which have formed in old explosion craters.

The track then weaves its way towards Whakapapa Village, with one more detour to the 20m Taranaki Falls – the best-known and most spectacular waterfall in the park.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us