I suspect I’m not alone in owning a closet full of packs; one for every type of adventure. Some of them date back a few years but are too cherished to be passed on or disposed of and, like old photographs, they each help elicit memories of specific adventures and moments in the hills. My pack museum also reflects the changing technologies and trends of the outdoor industry, as well as my own approach to outdoor recreation which over the years has seen me undertake bigger adventures while maintaining an increasingly minimal approach to equipment and pack weight.

Every pack tells a story, here are a few of mine.

Seven years old: the small blue framepack

I don’t recall the brand of my first pack, but it was a blue Cordura one, with a basic external frame of aluminium tubes, like a schoolboy-sized version of the Mountain Mule all the grownups used.

I remember looking out the cab window and watching it drift from side to side in the back of our ute as we zoomed around the Remutaka Hill road on our way to the Wairarapa.

We were setting out from Holdsworth Road end to walk to Mountain House on what would be my first overnight trip. Dad carried most of the food but he made me carry some too so that I’d have ‘my share’ of the load, along with my sleeping bag and spare clothes. I wore shorts and a bush shirt that was too big and looked more like a bush dress.

The walk to the hut was long and arduous and a bar in the pack’s frame dug into my back. I remember being distracted by the network of tree roots that wove their way over the forest floor like spaghetti junctions. The deep mud of Pig Flat was a lot of fun, but it nearly sucked the boots off my feet.

I felt unsettled by the quiet isolation of the forest. The wind made a creepy sound as it blew through the trees, tugging at the lichen, and it was misty and cold, like nowhere I’d ever been.

We could smell the smoke from Mountain House before we saw it. It was not a house at all but a lonely, rustic structure and was dark and scruffy inside. There were lots of flyspecks on the windows and a deep pit outside full of rubbish. Other trampers were there and it looked like I would have to sleep with people I didn’t know on one big platform.

Then Dad tried to make a joke and said that there were man-eating rats there. I thought he meant there was a man eating rats, which sounded terrifying. So I said I wanted to leave and tramp back to Holdsworth Lodge, where it was a bit less weird. Dad was probably disappointed, but we did it. I might not have been very brave, but the walk was a nascent demonstration of my endurance.

Early teens: Mum’s Fairydown

During my teens, I tramped at every opportunity. School holidays were often consumed by multi-day family tramping trips: from the Tararuas to Nelson Lakes and the North Island volcanoes. I was in the school tramping club, usually one of the youngest on trips, and was well accustomed to overnight adventures. I felt at home in the ranges, undeterred by bad weather and I was already more experienced than most of the teachers.

Climbing seemed preordained, born from a combination of Dad’s influence, TV documentaries and poring through books by Graeme Dingle, Reinhold Messner and Gaston Rebuffat.

The central North Island volcanoes are where many aspiring mountaineers first wield an ice axe or stamp their feet into rime-iced mountainsides. The Aotea College tramping club had led me to the Tararua Tramping Club, where my friend Gwilym and I joined many weekend trips. It was on one of these trips that I found myself descending Mt Tongariro in winter late one afternoon.

Our group was doing the ‘three peaks in a weekend’ trip, a foundation journey of basic mountaineering skills. We’d left Blyth Hut early on Saturday, cramponing up expansive snow bowls and then the upper slopes of Mt Ruapehu. The day ended with a wander down Waihohonu Ridge. I enjoyed the off-track travel and associated sense of adventure. Looking back, it was a formative trip and when I realised tramping didn’t have to be on track. After a night at Waihohonu Hut, we climbed Mt Ngauruhoe via its south-eastern slope, descended to the north and then climbed Mt Tongariro.

I grew fast through my early teens and Mum and Dad stopped buying me packs; I borrowed Mum’s Fairydown instead. I don’t recall the model, but it was big, burly and had a sleeping bag compartment. But this anecdote is not about my pack, it’s about someone else’s.

Descending Tongariro into the Mangatepopo Valley, we encountered a series of short bluffs. I was just figuring out my line when I heard our party leader shout out, followed by a loud thump.

One of the group had unshouldered his pack and casually dropped it down the short cliff, intending to climb down to it unencumbered. But instead of resting on the ledge, his pack had bounced, rolled forward and then begun a long tumble down the steep slope. I heard the man yell, ‘my camera!’ and then the pack dropped off a short ledge to land square on the top of its lid which plunged the long wooden ice axe strapped to it into the ground. The pack stood firmly fixed into the ground, 200m below, like a canvas obelisk. The camera still worked.

17 years old: Outside Lotus

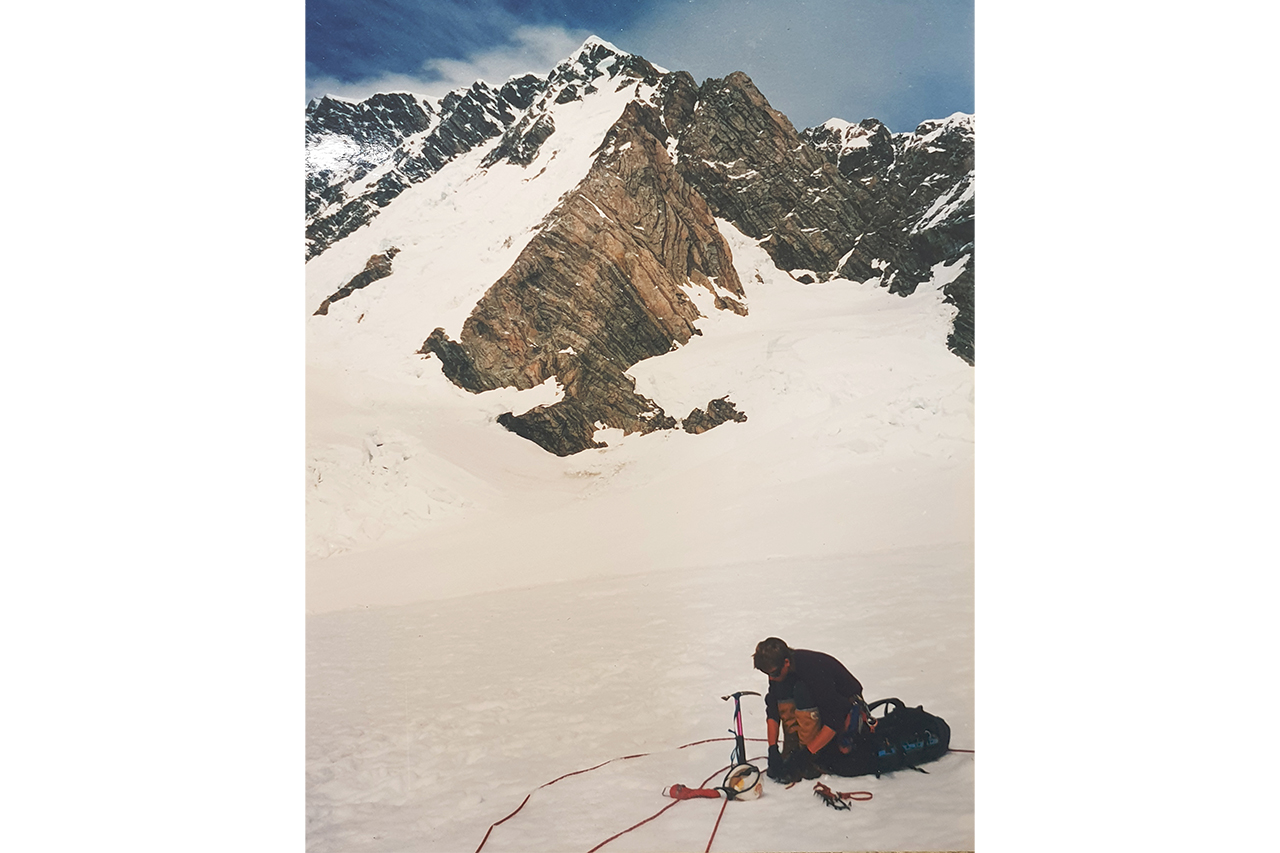

My path through mountain adventures led to a winter peak bagging trip in Nelson Lakes National Park. The following summer Gwilym and I were invited by two older climbers to spend a month at Aoraki/Mt Cook. It was the summer of 1988/89 and Aoraki-based mountaineering was still in its heyday.

I’d been given two special gifts for my birthday and Christmas; a proper mummy-shaped down sleeping bag and a large climbing pack. Back then, it was standard to have a pack in the region of 80-litres. It was used on every trip, whether a weekender or a 10-day journey. Mine was an Outside Lotus, a short-lived brand of New Zealand-made gear. I was so skinny that I couldn’t cinch the waist belt tight. If you were behind me, I’d have appeared as a giant blue canvas blob with two bony legs poking out.

I lugged that pack – full to the brim – from Husky Flat on the Ball Road, up the desolate moraines and white ice of the Tasman Glacier, to Beetham Hut. With a Sony Walkman in the lid, I listened to Dire Straits and Siouxsie and the Banshees during the long trudge.

The older two were much faster and I used to feel sick from the effort of staying with them in the dark on the alpine starts, but we climbed Aiguille Rouge and the West Ridge of Malte Brun back-to-back. I felt like a real climber, soloing along those red greywacke ridges, high in the sky, with Aoraki beckoning on the other side of the valley.

A few days later, I walked back down the Tasman Glacier with a lighter pack and a glow of satisfaction and confidence. I might have felt like a man, but I was still a clumsy 17-year-old careless enough to walk straight into a water-filled hole. Moulins are deep, narrow cavities formed by meltwater on a glacier’s surface. They’re often circular and can vary from less than a metre across to tens-of-metres. I’d fallen into the smaller size, not much wider than me and mercifully my oversized Outside Lotus caught on the edge and saved me from being submerged in the icy water.

26 Years old: Cactus Deepwinter

My climbing friend Gwilym had gone on to start Cactus Climbing, a pack manufacturing business which today is known as Cactus Equipment. My partner Hana and I worked for Cactus between climbing trips and long bicycle journeys exploring New Zealand.

We were a group of misfits: all in our 20s and eschewing the path of university, career and kids in favour of lifestyles that gave us maximum outdoor time and just enough money to get by.

One of the best products to emerge from Cactus was the Deepwinter pack. Roughly 60l with a simple lightweight harness and Cordura fabric, it made the 80l-plus canvas beasts seem like dinosaurs. Admittedly, we couldn’t fit everything in but that just meant you had too much stuff.

It was with a tightly packed Deepwinter that I hitchhiked to Fiordland’s Darran Mountains for the first time in 1997. My lightweight pack proved to be a versatile tool for a life-changing month of adventures there. New Zealand mountains didn’t have to include endless glacier plods and grappling with Weetbix.

44 years old: Exped Lightning 60

I got older and my packs got smaller. My philosophy of ‘maximum outdoor time’ continued through my 30s and into my 40s. The closest I came to a career was nearly 10 years working for the New Zealand Alpine Club as their in-house editor and designer. Many different packs embraced my shoulders during that time and during the latter part of my tenure, they were sometimes filled with photography gear.

I became an author and co-published my first photography book. While looking for another contract with my publisher I pitched the idea of tramping Te Araroa Trail and photographing it for a coffee table book. They agreed and a few months later, I was off down Ninety Mile Beach with three days of food and 8kg of photography kit which I carried all the way to Bluff, arriving 171 days later.

It felt as though this journey was my destiny – or one of them – as if the paths of my life had led to this challenge, where I was doing the thing I was supposed to do. With so many distractions and commitments in our lives, feeling truly ‘in the moment’ can be difficult to achieve, but I indulged it for nearly six months with nothing much to think about other than walking, eating, sleeping and using my craft to capture my surroundings.

My pack became more than a means to carry equipment; it became a companion. A very quiet and sometimes awkward companion perhaps, but one that was reliable and uncomplaining. When you walk for that long, some products are taken through their intended lifecycle, but that Lightning 60 was up to the task. Despite a couple of patches, I still use it.

Back in those carefree days in the mid-1990s, Cactus briefly called itself ‘Cactus Climbing Equipment & Space Exploration’. I always liked that: Cactus made products that enclosed space – or created spaces – in which to put gear. Maybe the second meaning was unintended, but packs also allow us to explore spaces in the great outdoors by providing a means to carry everything needed on our backs, under our own power. Humans have done this in one form or another for thousands of years.

Perhaps that’s why venturing into the wilderness with a pack on your back feels so good.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us