New Zealand is already feeling the heat from climate change, and those who work and play on our glaciers and mountains are witnessing the effects first-hand.

When Brooke Mellsop was a child in the 1990s, a walk to Franz Josef glacier was an annual excursion for the students at the tiny Franz Josef Glacier School on the West Coast.

Everyone was assigned a pair of hobnail boots in a thin drawstring bag. When the kids arrived at the glacier’s blue-tinged face, they laced up the boots and climbed the axe-cut ice steps onto the surface of the huge glacial tongue. Supervised by Brooke’s father, who owned the glacier guiding company, the children explored its ridges, crawled into caves and peered into the glistening turquoise depths.

Today, one generation on, school children no longer make the trek to the glacier that gave their community its name. The ice has retracted almost out of sight and, for most, out of reach.

Disappearing ice giants

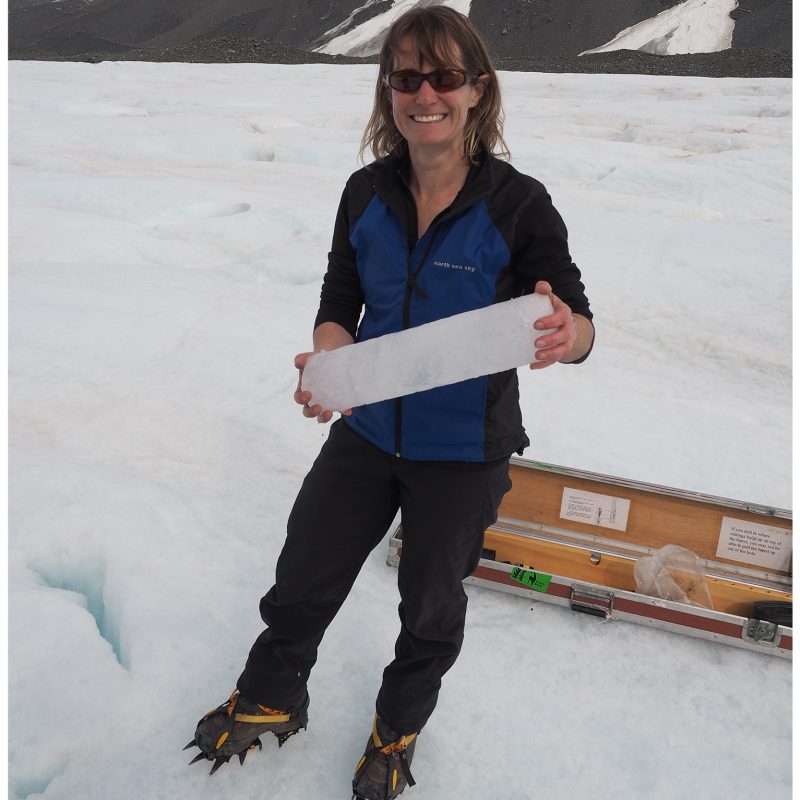

Scientists such as Lauren Vargo, a glaciologist at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, predict dramatic warming by 2090, especially in the mountains in summer. The North Island’s Central Plateau and parts of the Southern Alps could see average summer temperatures 3.5 degrees higher than they are now.

Glaciers are among the most visible indicators of warming that is already taking place. “It’s hard to visualise an increase of one degree or 10cm of sea-level rise, but you can see this big mass of ice getting smaller,” says Vargo.

Under worst-case projections, New Zealand will probably lose 90 per cent of its glacier ice. That means most smaller glaciers will disappear, and the big ones, like Haupapa/Tasman, Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere/Franz Josef and Te Moeka o Tuawe/Fox, will dwindle to stumpy, high-altitude rumps. Even under the most optimistic scenarios, some glaciers will still be lost because of warming already baked into the Earth’s system.

“Glaciers can’t lie,” says associate professor Heather Purdie, a glaciologist at the University of Canterbury, quoting late New Zealand glacier expert Trevor Chinn. While snow cover can vary dramatically from year to year, glaciers represent average temperatures, she explains – the difference between winter snow and summer melt.

A glacier is topped up by winter snow each year, but slight increases in summer temperatures can cause more ice to melt than the snow adds, so the glacier retreats. “Glaciers are really important barometers,” says Purdie. “If a glacier is shrinking, it’s warming up.”

Glaciers go through natural cycles of growth and recession. During the twentieth century, Fox and Franz Josef glaciers advanced and retreated roughly once a decade. Extreme lows were reached in the early 1980s. The glaciers then grew dramatically in the 1990s, receded, and grew again between 2004 and 2008.

But the melt happening now has outstripped natural cycles. All of New Zealand’s roughly 3000 glaciers are in retreat; over the past 50 years, a third of New Zealand’s glacier ice has melted. Overall, from the 1800s to 2014, Franz Josef and Fox glaciers have each lost around 3km in length. Since then, the rate of melt has increased. Fox has lost another 900m since 2014, and in 2017 slipped back past its previous all-time low of the 1980s. Visitors to platforms built to view the glacier now can see nothing but bare rock.

Every year at the end of summer, researchers from the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Science (NIWA) carry out an aerial survey of 50 glaciers in the Southern Alps. Vargo uses the detailed images of the Brewster Glacier in Mount Aspiring National Park to make precise 3D models of its overall mass and shape. She reports that this glacier’s level has dropped by an average of 14m in the last eight years.

Walking with giants

For centuries people have used the glaciers of Te Waipounamu as pathways through the mountains.

Māori traversed glaciers as they crossed over Kā-Tiritiri-o-te-Moana the Southern Alps to settle, trade pounamu and gather mahinga kai. Ngāi Tahu ancestors named the massive glacier above the Waiho River ‘Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere’ – tears of the avalanche maiden. Legend tells how Hine Hukatere took her lover Wawe into the mountains, where he slipped and fell to his death. Hine’s tears froze into frothy peaks of ice, forming the glacier.

In 1862 German-born geologist Julius Haast gave Kā Roimata o Hine Hukatere a new name, Franz Josef, in honour of the Austrian emperor.

A visit to the glacier became part of the ‘New Zealand Grand Tour’, and Victorian tourists strolled on the ice in full formal dress. In 1936 National Geographic described Franz Josef Glacier as ‘one of the most remarkable in the world’. Extending from the peaks into the temperate forest of the West Coast, it was also one of the most accessible.

The glacier was still relatively remarkable and accessible in 2010 when Michael Rooke began work as a glacier guide.

Over the following two years, though, it retreated hundreds of metres. The valley floor was left bare and dangerous, showered by rock falls from cliffs left unstable by the vanished ice. Under pressure to protect the health and safety of clients, in 2012 Rooke’s company ceased providing walking tours up the valley.

In the 14 years that Rooke has been guiding, the glacier has retracted 1.5km up the valley. He still leads trips, and says the experience of standing on the ice is undiminished.

These days, however, a helicopter tour is the only way for most people to get close to the ice, and clients are largely wealthy tourists. There are no more trips for the local children.“Getting up there would require five or six helicopters. It’s not feasible,” says teacher Sarah Gregory.

That’s a real loss, according to Rooke. “These glaciers are a huge identity touchstone, a cornerstone of the West Coast.” Without visiting them, it’s harder for today’s children to feel connected to these special places.

Crumbling highways

When he’s not guiding, Rooke climbs mountains and says that, apart from scientists, alpinists and mountaineers are some of the few people to really see the first-hand effects of climate change.

He remembers returning to a favourite spot last spring, expecting to see the ribbon of ice he’d climbed a year earlier. It had gone. “For the first few years I didn’t think about it much. I just thought, well, the mountains are dynamic. Everything changes. But then, over a decade, I started to recognise that they’re changing – but they’re never changing back. It’s always melting.”

NZ Mountain Safety Council is monitoring the impact of climate change on visitor access and safety, says chief executive Mike Daisley, who adds that vanishing ice has already increased the access difficulty of many beloved alpine routes.

“Where people could once rely on these ice and permanent snow passageways for reasonably safe access, some have now become completely impassable, or the risk of taking them on is just too high,” says Daisley. “Gardiner Hut, the historic Hooker Hut prior to its move, and Murchison Hut, for instance, were once safe refuges from storms or bases for climbing trips for mountaineers. But because of significant glacial retreat leaving behind unstable rock, these huts have been removed or closed.”

Back when they were fat and healthy, glaciers once filled the valleys, creating gentle ramps leading to alpine huts and the bases of many high peaks. “There are these beautiful stories of the mountaineers of old who would just walk up and over the mountains like it was nothing,” says Rooke. “Now, even with all our modern equipment and weather forecasting, you’d find it an incredible challenge to do what they did simply because of the terrain. It’s broken up so much.”

In 2015, while carrying out research for his 2021 book Uprising, Ngāi Tahu author Nic Low climbed over Copland Pass. According to Māori legend, the pass was first discovered by Ngāi Tahu woman Hinetamatea, who crossed the mountains from west to east with her two sons and their wives. Low writes that in Hinetamatea’s time, Hooker Glacier would have filled Hooker Valley, making it possible to step from the Copland ridge directly onto the glacier and then follow its mellow slope into the bird-rich lands beyond.

Low’s father tramped the route in the 1970s, when it was reasonably easy. It was more difficult on his second trip, in the 1990s. On his own research journey, when Low and his brother reached the end of the ridge they found themselves on a precipitous cliff. The glacier lay 150m below, and ‘a billion tonnes of rubble filled the valley, like the bombed ruins of Europe during the war,’ he wrote. After an exhausting, hairy descent down the collapsing moraine wall, Low concluded the route was now passable only by experienced mountaineers – meaning few Ngāi Tahu people will be able to follow this spectacular ancestral trail.

New lake

Mountaineers are noticing changes even on New Zealand’s coldest, highest mountains. Purdie, a recreational climber as well as a glaciologist, vividly remembers a recent ascent of The Nuns Veil in Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park, a route she had completed seven years earlier.

It was harder than she remembered and the top part of the slope seemed steeper. Then her ice axe went clear through the ice and hit rock. “That’s not a good sound because it means there’s bugger all ice there. There’s no doubt about it – you know it’s definitely thinning.”

The experience inspired a research project. Purdie and a colleague examined how the most popular route up Aoraki – via the Tasman and Linda glaciers – had changed since the 1800s. They combined historic accounts, maps, photographs and hut logbooks with surveys and interviews with modern climbers as well as measurements of glacier ice thickness over time.

The project found that since the first attempted ascent of Aoraki in 1882, the surface of Haupapa/Tasman Glacier had lowered by 200m. Where once mountaineers climbed up onto it, they now face a difficult, steep descent down the unstable moraine wall. In order to avoid the treacherous scree, many fly to Plateau Hut instead.

On the higher part of the route, up the Linda Glacier, a thinning trend was less obvious from photographs taken over 120 years. Purdie points out that snow and ice cover, and the depth and distribution of problematic crevasses and bergschrunds, vary considerably, seasonally and from year to year.

But mountain guides and recreational climbers she interviewed in 2018 did report an increase in the steepness of the upper Linda Glacier, and a marked shortening of the climbing season. Purdie and co-authors wrote: ‘through the 1980s and 1990s the route was in good condition from November to March, but since the 2000s, and particularly since around 2012, the route could be cut off [by crevasses] by mid-January’.

Some mountaineers see the changes as just another challenge. Nina and James Dickerhof climb often in Mount Aspiring National Park and south Westland’s Hooker Range. They’ve noticed widespread melting, and say it requires creativity and problem-solving to figure out alternate routes on the fly.

“I guess this is part of what makes it fun,” says Nina. Sometimes the melt will itself open up new possibilities. “For the places that we like to go, we can come up with as many examples where things have gotten easier as we can for things that have gotten harder.”

Purdie agrees that change doesn’t always mean loss. In 1990 a new lake appeared at the front of Haupapa/Tasman Glacier, formed by the same process that led to the formation of lakes Pūkaki, Tekapo and Ōhau at the end of the last ice age. She explains how, as a glacier recedes, meltwater becomes trapped behind the moraine walls, filling in the deep scours in the valley floor made over millennia. “It is a natural process, but what’s causing the warming and the extent of the warming isn’t natural anymore.”

This story was funded by NZ Mountain Safety Council and published exclusively by Wilderness.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us