I heard about the Three Passes Route when my daughter Emilie was six. We were at Anti Crow Hut on an overnighter when a fit group of trampers, ice axes strapped to their packs, stormed past up the Waimakariri River. We watched in awe, convinced the 53km transalpine traverse of the Southern Alps was far beyond our reach.

But time and experience can reshape what once seemed impossible. Four years later Emilie and I found ourselves at the start of the route.

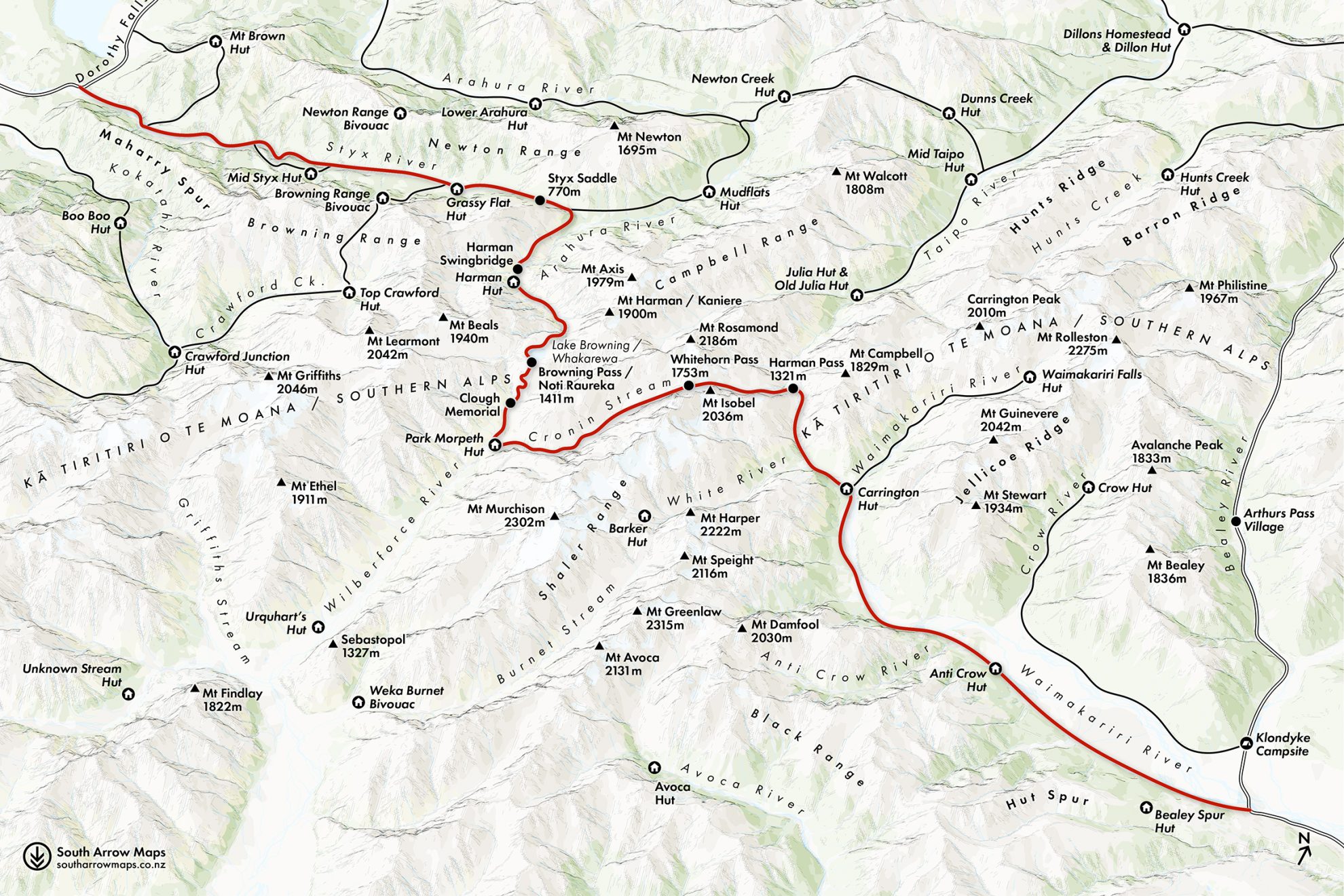

The Three Passes is an iconic crossing of the Southern Alps, linking Arthur’s Pass National Park to the wild West Coast. It traverses Harman Pass (1321m), Whitehorn Pass (1753m) and Browning Pass/Nōti Raureka (1411m), rugged river valleys, alpine meadows and the remnants of a once mighty glacier. With nearly 3000m of elevation gain, it’s a serious undertaking for experienced backcountry trampers and requires route-finding skills, river-crossing knowledge and, at times, the use of ice axes and crampons.

Emilie, my friend Nadia and I teamed up with four Hokitika Tramping Club members to tackle the route from east to west. It can be done either way, but heading west is more straightforward and avoids a steep descent down Browning Pass/Nōti Raureka.

This pass has long been an important alpine passage. It played a significant role in Ngāi Tahu gaining mana whenua of Te Tai Poutini (territorial rights of the West Coast) and control of the valuable pounamu trade. It was later used by Pākehā gold prospectors and pioneering pastoralists. The route was surveyed in the late 1800s as an alternative to the Arthur’s Pass route, and a track was cut in 1865–66 to drive sheep from Canterbury to Hokitika. It quickly fell into disuse, and today it’s crossed by trampers drawn to its inherent challenge and history.

After catching the bus from Greymouth to Klondyke Corner, with an emergency coffee stop in Arthur’s Pass, we hit the wide-open expanse of the Waimakariri River Valley just as the morning sun was sucking the last of the dew from the long grass. Crickets were singing and the heat made us aware of our heavy packs, loaded with provisions for the five days ahead. Our group carried micro spikes and lightweight ice axes as safety precautions for the glacier travel to Whitehorn Pass, plus tents in case huts were full over the long weekend.

Jagged peaks rose from the valley floor, looming over us as we made our way inland. The first day’s plan was to walk past Carrington Hut, cross White River, scale the Taipoiti River gorge up to Harman Pass and make camp by Ariels Tarns. It was not to be, as one of our group, a teenager travelling with her mother, was unwell and unable to keep up. The pair opted to stay at Carrington Hut and make their way out the next day. Our group, now five, decided to camp on the terraces of White River on a mossy bank just wide enough for our three tents.

Morning coffee was brewed in the dark with stars twinkling overhead, before we packed up dew-damp tents and began the long boulder-hop up the Taipoiti River Gorge. Low mist hid the sheer cliffs above our heads, waterfalls tinkled from unseen heights, and gentians and Mount Cook buttercups were plentiful as we gained height. The gorge gave way to a series of sloping tussock shelves and eventually, after 400m of climbing, we popped out onto Harman Pass shrouded in mist. We consoled ourselves at the lack of view, thinking that if we’d camped up here we would have been wandering up Whitehorn Pass in cloud as thick as soup. As we hunkered down to prepare another coffee behind a stone wall built by other trampers, the mist lifted, revealing the stunning blue-green of Ariels Tarns.

The trail now turns south, and we picked our way up the moraine of shattered stone once held tightly by ice. The loose shards of rock had to be navigated with the utmost care, and it took us several hours. The narrow chute up to Whitehorn Pass was now clear of mist, and we could see huge chunks of residual glacier wedged in the rocky tunnel, with meltwater trickling underneath.

The Whitehorn Glacier has changed exponentially in recent years. The ice field, once a continuous ice sheet from near Harman Pass to Whitehorn Pass, has shrunk dramatically. Large sections have melted away, and others have fractured as their underlying ice caves collapsed. The glacier is another casualty of a warming climate, and recent surveys by NIWA suggest that 40 per cent of monitored glaciers will be gone in a decade. There used to be a sustained snowfield up the Whitehorn; now only small sections of perennial snow remain.

It was slow going on the far side of Whitehorn Pass through the boulders and tussock-covered Cronin streambed. Just before Park Morpeth Hut we had a chance to view the towering face of Browning Pass in the fading light. Then light rain turned into a heavy downpour as we navigated the final hour of the streambed, and we were delighted to arrive at the six-bunk hut – only to find it was full. Space was made for us, however, and some of our group slept in the hut while Jaci and Brent braved the rain in a tent. By nightfall, four other tents had sprung up – it was clearly a popular route for a long weekend.

The rain had stopped by morning, and bright blue skies promised great weather to tackle our third pass in as many days – Browning Pass/Nōti Raureka, the steepest section of the route. One of the lowest passes across the Southern Alps, it leads from the Wilberforce River, a tributary of the Rakaia River, to the Arahura River.

We walked up the true left of the Wilberforce and forded the knee-deep flow after it joined with Hall Creek opposite Clough Memorial. The Wilberforce may be benign in low flow, but in heavy rain it can be raging.

The small pyramid-shaped memorial stands as a warning: in 1929 James Park and John Morpeth drowned here, prompting Canterbury Mountaineering Club to build Park Morpeth Hut. In 1956 16-year-old Allan Clough also drowned while fording the river, and his grieving friends built the memorial in his honour. His name was also attributed to the former Clough Cableway, which spanned White River near Carrington Hut until its removal by DOC in 2024. White River is now only crossable in low flows.

The 500m climb from the head of the Wilberforce to Nōti Raureka is a relentless ascent up a narrow track that zigzags sharply through loose scree and tussock-covered slopes. Each step requires careful footing, and exposed sections demand full concentration. Emilie and I decided to take a ‘short-cut’ by heading directly up the scree slope, hauling ourselves up with handfuls of tussock, hebe and dracophyllum. Our legs burned with the effort, and our packs felt heavier with every metre gained, but we finally crested the pass and our exhaustion melted away. Laid out before us was Lake Browning Whakarewa, a brilliant blue expanse of water cradled by tussock, herb fields and clusters of alpine flowers swaying in a gentle breeze.

Coffee was brewed, its rich aroma curling into the morning air, and a fruit loaf was shared. As we savoured each bite we gazed down at the Wilberforce River, its braided channels weaving like silver threads through the vast, windswept valley below.

A low mist tumbling down from the Campbell Range and racing across the surface of the lake deterred even the keenest among us from stripping off for a celebratory swim. We shouldered packs and set off, skirting the shores of the lake until the track began descending steeply into the headwaters of the Arahura River catchment.

The drier beech forests of the east coast contrasted starkly with the western side of the Main Divide, which pulsed with life fed by the moisture drifting up from the dense rainforest. Waterfalls tumbled down mossy cliffs, their steady roar blending with the warbling calls of riroriro and korimako.

After several kilometres of rock-hopping down a tumbling creek, navigating slick boulders and skirting deep, clear pools, the track veered sharply upward taking us winding through dense greenery for another kilometre until Harman Hut emerged. It was now late afternoon and the swirling mist had settled into steady West Coast rain.

We shared the cramped hut with a group of seven hunters, and the next morning began with an unexpected twist. When the hunting party departed at 5am they slid the outside bolt shut, locking us inside. Emilie made the alarming discovery – we were trapped. Fortunately, we managed to remove a few panes from the louvre window and Emilie squeezed through the gap to unlock the door and free us.

Back on the track, we relished the excitement of the ladder ascent and the airy views from the Harman swingbridge, where the river plunged into the gorge beneath. Further along, the notoriously boggy Styx Saddle lived up to its reputation. We found ourselves thrashing through head-high tussocks, playing an unintentional game of peekaboo as we struggled to stay on course.

We covered the 5km from Harman Hut to Grassy Flat Hut in just under three hours and enjoyed a swim in the river and a lazy afternoon soaking up the surroundings.

As we exited via the Styx River on the fifth day, I reflected on how much had changed – not just in the land, but in us. Four years ago, Emilie and I had stood at the mouth of the Waimakariri Valley, seeing only an impenetrable wall of mountains. Now, after thousands of kilometres together – across Te Araroa and through some of New Zealand’s wildest places – those once-daunting landscapes were becoming familiar ground. With each journey our skills and confidence have grown, revealing not only the mountains but also our capacity to navigate them.

The Three Passes itself remains a benchmark for trampers despite the glacial recession. It’s a rite of passage for those drawn to the heart of New Zealand’s wilderness. Its challenges change, but its essence remains: an unforgettable journey through time and terrain.

Several hundred years ago, crossing the Three Passes would have meant crossing a national ‘border’. On the eastern side of the alps you were in Ngāi Tahu country. Set foot in the west, and you were entering the domain of Kāti Wairaki, the tribe that controlled pounamu in those days. The two peoples were distantly related, and oral history says a senior Ngāi Tahu party had visited the Coast to learn spiritual knowledge from Kāti Wairaki priests – though tensions rose when the visitors paid more attention to the local women than their studies. Things came to a head when a young Kāti Wairaki woman named Raureka stormed off into the mountains after a fight with her family and discovered the route now known as Nōti Raureka, or Browning Pass. She married into Ngāi Tahu and shared with them her route to the Arahura River, the most famous pounamu source in the motu. Ngāi Tahu trading and war parties crossed the alpine passes, and skirmishes escalated into major battles at Lake Māhinapua and Kōtuku-whakaoho/Lake Brunner. Ultimately, Ngāi Tahu was victorious and established mana whenua on the West Coast. Kāti Wairaki became part of Ngāi Tahu.

1. Waimakariri River

The route starts in the braided channels of the Waimakariri River, a lifeline of the Canterbury high country. Trampers follow it upriver across shingle beds into the mountains, where the valley narrows and more rugged terrain awaits. The Waimakariri’s ever-changing flow makes river crossings a key challenge, particularly after heavy rain.

2. Harman Pass (1321m)

This is the first of the three passes. It marks the transition from the Waimakariri watershed into the Taipo River catchment. It’s named after surveyor Joseph Harman and is reached via a steep ascent through the boulder-strewn Taipoiti River. The pass, which is often shrouded in mist, provides a dramatic entry into the alpine, with jagged peaks on either side and Ariels Tarns just beyond.

3. Whitehorn Glacier

A shrinking remnant of past ice ages, Whitehorn Glacier clings to the flanks of its namesake pass. It was once a formidable ice sheet, but now lies fractured, with exposed moraine marking its retreat. Crossing its lingering icefields remains a highlight of the route and offers a sobering glimpse into the effects of climate change in the Southern Alps.

4. Park Morpeth Hut

This six-bunk hut is nestled in the upper Wilberforce Valley. It’s a Canterbury Mountaineering Club hut built in 1931 in memory of James Park and John Morpeth who drowned in the Burnett, a swift-flowing stream that drains into the Wilberforce River. Materials were carried in by packhorse. Hut fees are paid directly to CMC.

5. Browning Pass/Nōti Raureka (1411m)

This is an ancient pounamu trade route and holds deep significance for Māori, particularly Ngāi Tahu. The steep, 500m ascent from the head of the Wilberforce tests weary legs, but the reward is breathtaking – Lake Browning’s brilliant blue waters, framed by golden tussock and delicate alpine flora.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us