The Old Ghost Road is like no other trail in Aotearoa. It’s one of New Zealand’s 23 Great Rides, yet half the users are now trampers. Although it’s on conservation land, it is managed by a trust, and hundreds of volunteers worked alongside professional contractors to build it. Planning and construction of the OGR took eight years and more than 26,000 volunteer hours. It required engineering and technical innovation, included 16 new bridges and four new huts and received huge buy-in from the community.

In the past 10 years over 100,000 people have ridden, walked or run the OGR, and still they come. The trail now generates $12.8m for the region each year. It enables environmental restoration, a youth leadership programme, a popular annual fundraising ultra run event, and remains strongly all about community. The locals are justifiably proud.

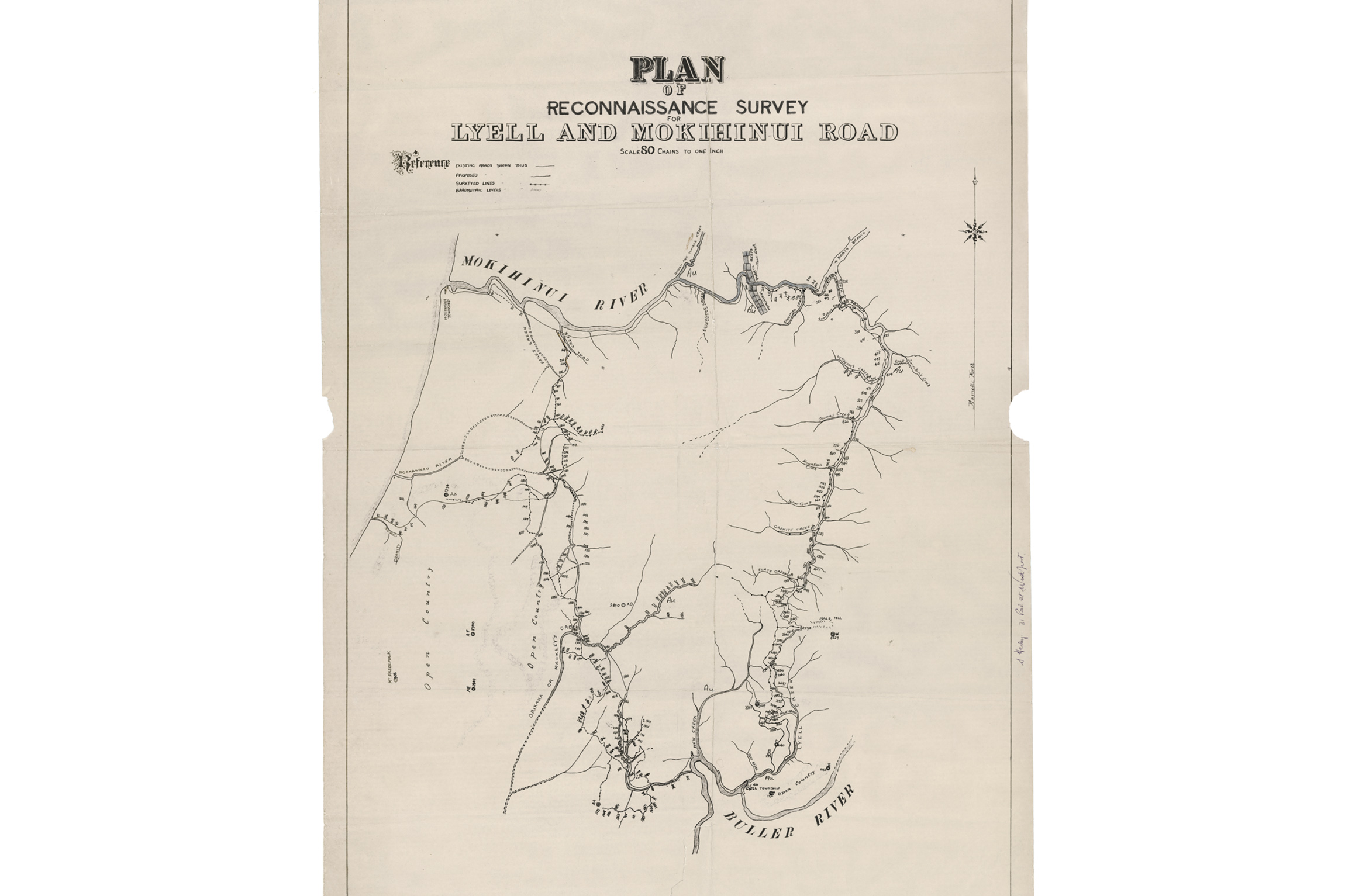

It all started with an old miners’ map that showed a dray road linking the former goldmining settlements of Lyell and Seddonville via the forested wilderness of the Lyell and South Mōkihinui valleys. A 2007 search by Marion Boatwright and local bushman Steve Stack showed that only part of the road was formed. They decided to open it up anyway, starting from Lyell, as a walking track. The Mōkihinui-Lyell Backcountry Trust (MLBT) was formed to tackle the job, with Phil Rossiter in charge. Boatwright describes Rossiter, who is still chair of the trust, as “savvy, and a mover and shaker who keeps people working together”.

At the same time, at the northern Mōkihinui end, Meridian Energy was proposing a hydro development: a high dam and 14km lake that would drown forest in the Mōkihinui valley and flood an old miners’ track that the MLBT planned to link up with. The MLBT entered discussions with Meridian who, as part of social and environmental compensation, contributed $20,000 seed funding for the trust to explore recreational opportunities and a potential higher-level walking track through the gorge.

In 2009 the MLBT’s focus changed. Ngā Haerenga New Zealand Cycle Trails was developing a network of trails aimed at driving regional economies. MLBT applied for funding, was accepted, and changed their plans. The walking track would be a dual-use walking and cycling trail.

Building mountain-bike trails in the wilderness was pioneering stuff back then, especially on this scale. Local man Jim McIlraith cut his trail-building teeth with a shovel on the OGR and now runs the highly regarded WestReef trail construction team. Mountain-bike track design guru Hamish Seaton introduced new LiDAR aerial imaging and computer modelling to determine the most environmentally sensitive, consistently graded and feasible ways to go. You can get through anything with brute force, but less excavation means less impact and less cost, says Seaton. One quarter of the construction was done by volunteers – hundreds of them – who stayed in the new huts, breaking rocks and shifting shingle by hand.

When, like the stymied goldminers, the team couldn’t find a way from Lyell Saddle through the south Mōkihinui Valley, they went bold. They took the trail over the tops, along granite ridgelines and in and out of rocky gullies. It was arduous and technically challenging but added subalpine landscapes and views that helped make the OGR the stunning, dynamic journey it is today.

But hanging over all this hard work and resolve were Meridian’s hydro plans for the Mōkihinui, the South Island’s third-largest river. At the time, this wilderness was classified as stewardship land, which has less protection than a national park, and in 2010 Meridian received resource consent for the proposal. Protests raged against the hydro proposal and Meridian faced Environment Court appeals from DOC and other groups. In 2012 the scheme was dropped, and within days an OGR track-building crew was at work in the Mōkihinui, resurrecting the northern end of that old miners’ track. Teams were now working from both ends.

Appropriately, on a wet October morning in 2015 at Solemn Saddle, where the trail crosses into the massive Mōkihinui catchment, two excavators met and ‘kissed’, signalling the joining of the two ends of the trail. Rossiter recalls: “A small crowd had gathered and, when the buckets touched, a wave of emotion welled up … I was totally unprepared for how it affected me.”

Rossiter’s emotion that day was testament to the spirit, grit, passion and energy that was poured into the building of the trail, and to the community that drove it and to this day remains staunchly proud. He is still bewildered by the sheer number of volunteers who assisted, some from overseas and often at great personal cost.

There were also low points. Some naysayers were concerned about the trust’s motives, potential degradation of natural landscapes, or they simply didn’t like the idea: “That was hard to bear, especially when you knew the intentions and integrity of the people involved,” says Rossiter. “As a society, the ability to have respectful discourse when there are differing views seems to be an increasing challenge.”

Mike Slater, DOC West Coast conservator at the time, says that although the development wasn’t a DOC project, it was on DOC-managed land and needed to meet standards. “From a DOC perspective, environmental compliance and maintaining appropriate track standards were really important,” he says. “The building of the Old Ghost Road was driven by an enthusiastic community group operating on a shoestring, and Phil and everyone involved developed a really good relationship with DOC. Nothing about the final trail left me with any concerns.”

It’s worth noting that in 2019 most of the OGR, including the hydro-threatened Mōkininui valley, was added to Kahurangi National Park. Rossiter says this vindicated what many already knew: that it is a special area deserving of such status.

Ten years on, the lessons learned have been enormous, says Rossiter. A big one was the user fee. Initially, hut fees were charged per night, as per the DOC model. But bikers only stayed one or two nights: “Very quickly, we learned that we were not close to making ends meet, and we had no financial backup,” says Rossiter. “We had to make a change that was sustainable and fair. We didn’t want to simply ratchet up the per-night fee as that might have encouraged people to rush their trip and they wouldn’t get the same enjoyment. It also raised safety issues.”

In 2017 the trust decided to charge a flat fee for track use, no matter how many nights a person stayed (though not exceeding one night per hut). That change saved the trail, says Rossiter. “The average length of visits grew to more than double the duration,” he says. “Bikers were no longer rushing through to save a night’s hut fee. Day riders are an anomaly, but there aren’t many compared with those who stay, and some make a donation.”

All track fees are reinvested into maintenance, supplies and conservation efforts.

Around 2019, safety fences were added along the riskiest sections. Although some grumbled about spoiling the natural landscape and mollycoddling bikers, Rossiter is unfazed: “This was about meeting legal standards, and there had already been several lucky escapes. The barriers affect a very small portion of the trail and are low volume by design. Time has shown them to be a valuable addition. Some users have actually credited them with saving their life.”

Although the hut living areas have been enlarged, the trust has not been tempted to extend sleeping capacity despite the trail’s popularity.

“If every bed in every hut and camping space is full, that means there is one person per kilometre on the track, mostly heading in the same direction, and this offers an intimate experience with the landscape,” says Rossiter. “That’s the beauty of the trust managing the trail: we can adapt as we need. With the benefit of 18 years of reflection, we deeply value the autonomy that we have been given and that trust management has allowed, especially so we can pursue the wider aspirations we hold for the trail. Notably, we’re seeing trail management arrangements around New Zealand follow suit as others see the benefit of the trust approach.”

The OGR brings wider benefits to the community. Each year, visitors to the OGR contribute $12.8m to the region. Rossiter: “That’s massive for a district like this. Of all users, 93 per cent come here just for the OGR. They spend almost $600 per person per trip which is spread around car shuttles, food, accommodation and bike hire. New businesses have been established and 12 existing businesses have expanded or added new services because of the trail.”

The environment also benefits: the OGR has enabled access for large-scale predator control, none of which was happening before the trail was built. “We have 1000 traps across the trail, serviced by a mix of volunteers and contractors,” says Rossiter. “For about seven months of the year, volunteer hut wardens are particularly involved in trapping as they bike or walk in and out of the trail. Since 2015 we have caught more than 7850 mustelids and rats. That doesn’t go unnoticed. DOC’s 1080 applications have added to our impact. We get huge feedback about the birdlife – that it’s the best people have heard on any track in New Zealand.”

In partnership with Whenua Iti Outdoors, the trust also supports a Kaitiaki Leadership Programme that’s based at the Rough and Tumble Lodge and focuses on empowering youth leadership through connection with nature.

And the benefits look likely to continue. In alignment with the broad-reaching Kotahitanga mō te Taiao Alliance, the trust is currently scoping a potential landscape-scale mainland island covering 100,000ha across the OGR, Mōkihinui and Buller/Kawatiri catchments westward to the coast. Still in its early stages, engagement with local communities and stakeholders will be the priority once scoping and testing are completed. Rossiter believes that establishing a landscape-scale predator-free sanctuary would set new standards for environmental stewardship in adventure tourism.

Community backing for the OGR is strong. A near-completed evaluation of all NZ Great Rides reveals that close to 100 per cent of local respondents agree the OGR is valued by and a source of pride for the local community and has been a catalyst for community development.

Rossiter sees a more profound picture. “As the Old Ghost Road team and wider West Coast community celebrate this anniversary of achievement, their story is not only about building a trail. It’s about reconnecting people with place, history and the power of grassroots action.”

He says that user feedback from both bikers and walkers shows that the OGR is more than just a recreational asset. “I love that the main motivators for visiting the OGR are exercise, relaxation, to escape the daily pressures of life, to experience or learn about the natural environment and to spend time with family and friends. And I love that a significant proportion of users indicate that, as a result of their OGR experience, their sense of wellbeing or mental health has improved, they have developed closer relationships, and they understand more about and are more determined to protect the natural environment and culture and heritage.

“All this points to what I believe is one of the single biggest lessons and realisations about the Old Ghost Road, and that is how powerful and important trails are to our future. The initial case was one of economic contribution and diversity for a struggling district, but we really underestimated how trails contribute to so many other important social and environmental facets of life. As one colleague suggested to me, ‘The road to carbon neutrality, zero road deaths, healthier and happier communities and regenerative tourism isn’t a road, it’s a trail.’”

The OGR has shown this first hand. “Trails foster communities, connections between people and nature, movement and resilience – all increasingly threatened yet essential things for the human condition and the future of the planet.”

Looking ahead, Rossiter says the future for the OGR holds both challenge and opportunity. “When will the impacts of climate change become too great to bear? Where will the next era of custodians come from to take the trail forward? Will people still seek the things a backcountry trail experience offers, such that the trail is viable to maintain and operate? How might we replace key assets like bridges and huts at their end of life? But all these things bring corresponding opportunities. Finding the time to look ahead, contemplate these and address them is a big part of our future: pushing ourselves to consider what more we may be able to do for people and the planet, rather than simply asking what we can get away with.”

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us