By Lily Duval, Sam Gibson, Sam Harrison, Leigh Hopkinson, Nic Low, Kathy Ombler, Michael Szabo and Mark Watson

If Aotearoa is the centre of the outdoor universe – and it clearly is – then Aoraki Mount Cook National Park might just be its heart. It is home to the most jaw-dropping alpine landscapes, the scene of the country’s formative mountaineering years, and the place that has inspired many a tramper to chuck on crampons and aim for the sky.

It’s also the heart of Maori iwi Ngāi Tahu’s identity, with sacred places around Aoraki’s base. Ngāi Tahu asks that climbers respect the mountain’s tapu status by carrying out their waste and refraining from standing on the summit. The mountain stands as the tribe’s oldest ancestor, tied to the creation of the world.

It’s a world in flux, however, as climate change affects glacier access and turns former classics into marginal routes (see Copland Pass Nōti Hinetamatea).

A is also for…

Avalanche Peak, the most popular day trip in Arthur’s Pass; Abel Tasman National Park, renowned for its golden beaches and family-friendly coast track; and Aotea Great Barrier Island, home of the tākoketai black petrel. And let’s not forget Aurora Australis, the Southern Lights.

It starts slowly … bubbles begin to form … and at 100℃ something magical happens. ‘The billy’s boiling!’ Rapid footsteps answer the call, hands reach for the cooker, and minds shift to where the tea bags are.

People have been boiling the billy in New Zealand since the first Pākehā arrived.

The humble billy is a staple of tramping culture, retaining a certain allure in today’s high-tech world. The phrase ‘I’ll put the billy on’ is sure to evoke warm memories in any hiker.

B is also for…

Backcountry Trust, the organisation behind the restoration of over 280 huts; Rotomairewhenua Blue Lake, the clearest natural freshwater in the world, regarded as tapu by local iwi, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō; and bush-bashing, the art of making one’s way through undergrowth without a track.

As far as transalpine tramps go, Copland Pass has – had – it all: a jaunt up the mighty Hooker Glacier, an airy ridge to ascend with stunning views of Aoraki, a night in a corrugated iron shelter, a descent to forests dense with birdlife and a dip in Welcome Flats hot springs to finish.

The journey was first made by Hinetamatea, an ancestor of the Kāti Mahaki hapū of Ngāi Tahu, who crossed west to east with her two sons and their wives. Since then, generations of Kāti Mahaki people have worked on the track, built huts, climbed in the area and helped guide the tourists who once traversed the route. These days the crowds are largely confined to the western side; glacial recession and rockfall danger on the Hooker side means the full trip is now for mountaineers.

C is also for…

Clubs – hundreds throughout the motu bring together like-minded people, knowledge and skills; and cottage industries, from the 1960s Mountain Mule to the current wave of small brands making custom kit.

Love them or hate them, deer – released in 1861 – in a strange way underpin the adventurous way of life in Aotearoa. Recreational hunters couldn’t keep them in check, and in the 1930s the government established teams of deer cullers.

Some of these cullers built the first backcountry huts, many hand-adzed from the clearings in which they stand today. When the New Zealand Forest Service took over deer control in 1956, a network of tracks was created, huts and bivs were built that today form the core of the back country hut network.

D is also for…

Dusky Track, arguably New Zealand’s most difficult, stretching 84km from Lake Manapōuri to Hauroko; The Dragons Teeth high route, a revered sidle across the ridge south of Mt Douglas; and Department of Conservation, the government agency tasked with managing New Zealand’s outdoor heritage.

Aotearoa is full of fascinating insects, many of which only emerge after nightfall.

Darkness has a way of transforming the landscape. All that’s needed is curiosity and a torch to unlock the miniature wonders of the night. A tree that seemed unremarkable by day can be a six-legged nightclub after sunset. There are cave wētā with antennae twice as long as their bodies, and golden bush cockroaches that munch on organic detritus. Check the leaf litter at your feet for glossy black predatory beetles, barrel-shaped ground wētā or invertebrates like velvet worms.

E is also for…

Every F’ing Inch, the catch cry of fervent thru-hikers; the Eyre Mountains Taka Ra Haka, Southland’s highest; and earplugs (see Z).

Field Hut, built in 1924, is New Zealand’s earliest surviving purpose-built public tramping hut. Construction was funded with a donation from Tararua Tramping Club’s inaugural president, MP William Field. It took over five months to build, and, following completion, the hut has hosted a century of trampers united in their appreciation of a dry place to rest as they venture over the Southern Crossing of the Tararua Range. Field Hut is recognised as a Category 1 Historic Place.

F is also for…

Fiordland National Park, 1.2 million hectares of rainforest, ice-carved fiords and seemingly impenetrable mountains; the Forest Service, DOC’s precursor; and Freda de Faur, in 1910 the first woman to climb Aoraki Mt Cook.

‘I was overwhelmed with astonishment, so many beautiful and novel wild flowers and plants richly repaid me the toil of the journey and the ascent.’ The rapture expressed by botanist William Colenso in the 1880s on the Ruahine tops is surely akin to that felt by today’s trampers when greeted by tiny, hardy alpine delights after a staunch climb above the bushline.

The snow berry, named Gaultheria colensoi after the botanist, was one of many alpine species Colenso identified during collecting expeditions on the Ruahine Range. That’s collecting with a capital C, as he recounted: ‘I pulled off my jacket and made a bag of it. In went Celmisias, Ranunculous, elegant Wahlenbergia and beautiful Veronica. I added thereto my shirt and got an excellent bag for Ourisias and Euphrasias, Gentians and Dracophyllums. I also stowed in my hat Astelias, Calthas, and Gaultherias’.

Some of this profusion has since vanished thanks to browsing animals, but hardy alpine species will still reward a tramper for the climb. And of course, unlike Colenso, today photos and memories are taken, not plants.

G is also for…

Great Walks, all 11 of them; Gertrude Saddle and its great granite slabs; the Greenstone–Caples circuit, valley tramping at its finest; and glaciers, which have shrunk 29 per cent since 2000.

Sharing huts is like a social experiment in which total strangers cook, eat, ablute and sleep next to each other. You might enjoy chatting with these folk; you might also never want to see them again. What matters is that, for at least one night, you’re sharing a small, remote shelter, so you need to get on.

Hut etiquette (common sense?) includes safety, and it goes like this. Leave boots, poles and wet coat on the verandah, write your name and trip intentions in the hut book and keep your gear on your bunk. Cook on the bench provided, not on wooden tables, then tidy your stuff away, leaving space for others. Brush your teeth at the outside sink, and before leaving, put up your mattress, wipe the benches and sweep the floor. Make sure the fire is out and place ashes in the container provided; leave dry wood for the next people: chop some kindling and, if wood isn’t supplied, gather dead or fallen branches.

In the old days, there’d always be a billy on the boil (see B). Feel free to resurrect that lovely tradition.

H is also for…

Hooker Hut, the oldest in Aoraki Mount Cook National Park; Holly Hut, the popular pitstop on Taranaki Maunga’s Round the Mountain; and helicopter, in case you ever need one.

Deep in the hills behind Hokitika is New Zealand’s most sought-after remote hut. Built in 1970, Ivory Lake Hut takes its name from the lake beside it, which was formed early in the 1950s by the recession of the Ivory Glacier. It’s surrounded by impenetrable bush and high mountains, and initially catered for glaciologists monitoring the shrinking ice field. Few others visited. That changed in 2014 when American Backpacker magazine hailed Ivory Lake Hut as ‘the best backcountry hut in the world’. Two years later, Wilderness readers crowned it ‘Hut of the Year’. Today, the glacier is all but gone, but the area’s epic beauty remains a drawcard.

I is also for…

Inland Track, Tasman’s rugged alternative to the Abel Tasman Coast Track, and Inland Pack Track, which meanders through craggy West Coast jungle.

The old hut is supposedly haunted by the ghost of either Julia or Mary Griffin. In 1876, the girls, aged 8 and 11, were sent up Taipo River to retrieve cattle and never came home. It’s one of several huts where trampers have reported spooky happenings, including footsteps outside and the feeling of being watched. Others include Dillions Homestead Hut, Powell Hut, and Hooker Hut.

J is also for…

Jubilee Hut, a quality hut in a sunny spot in Otago’s Silverpeaks Scenic Reserve, and Jumbo Hut, on the classic Tararua loop, the Mt Holdsworth-Jumbo Circuit.

Everyone loves kea: they’re as Kiwi as ‘kia ora’. Most trampers have had a close encounter with the birds’ cheeky antics and know they’re as fascinated with us as we are with them.

But kea haven’t always been so well regarded. Due to the mistaken belief that kea were sheep killers, a hunting bounty was introduced in 1860. Over 150,000 birds were killed before they were fully protected in 1986.

This Southern Alps icon comes equipped with alpine gear: a strong pointed bill for an icepick, claws like crampons to clamber up frozen snow and feet like skis to slide down a hut roof.

They’re playful, intelligent and always up for a challenge.

K is also for…

Kiwi, best spotted in the wilds of Rakiura Stewart Island; mighty kauri, such as 2000-year-old Tāne Mahuta; Kahurangi’s karst country; and key swaps, when you entrust your car keys to a stranger and end up making new friends.

The world is changed. That’s the opening line of J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic, and in New Zealand, it’s a fitting description of the impact of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. People throughout the world have come to associate the soaring heights of Kā Tiritiri o te Moana, the Southern Alps, with the prose of Tolkien. No longer is Mt Sunday just a hill near Ashburton; it is Edoras, home of the Rohirrim. Mt Owen has become Dimrill Dale, Ngāuruhoe, the face of Mordor. But while marvelling at these vestiges of Jackson’s Middle-Earth, take a moment to remember that these places were interwoven in the stories of tangata whenua long before Tolkien put pen to paper.

L is also for…

Long weekends and soul-saving sojourns in the hills; Lake Nerine, cradled high in the Humboldt Mountains; and long drops (see V).

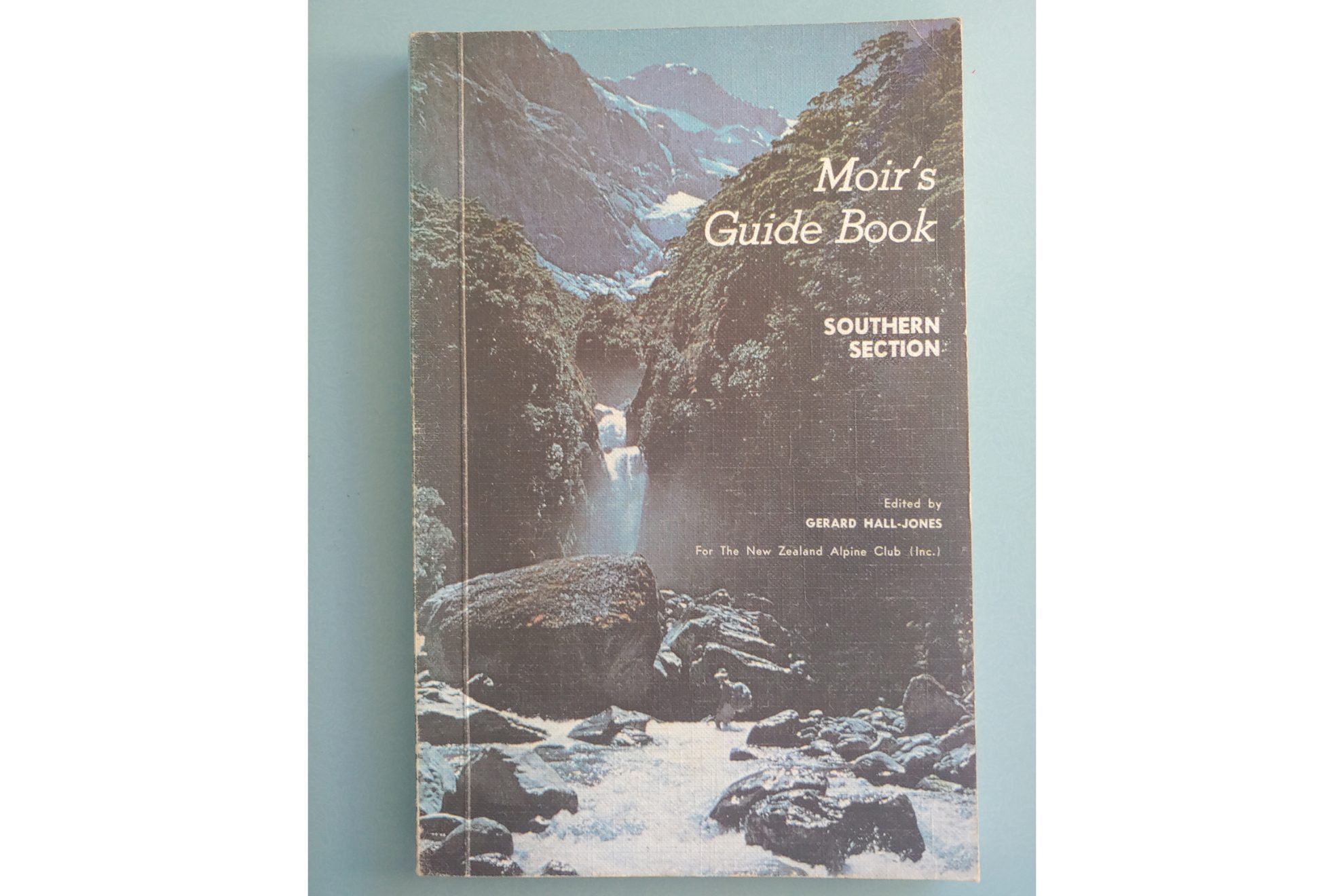

A must-have for off-track trampers, hunters and mountaineers in the southern South Island for the past 100 years, Moir’s Guide is the iconic New Zealand backcountry guidebook. First published in 1925 by George Moir as a guide for motorists visiting the ‘Great Southern Lakes’, editorship has been passed from one generation of backcountry legends to the next, making it a truly living document. Regardless of whether you are climbing next to a cataract or clinging to an arete, the wisdom and poetic phrasing of Moir’s Guide will be always appreciated.

M is also for…

Mates (where would we be without them?); merino, for keeping us warm and less stinky; and the Milford Track, the most famous walk in New Zealand.

This strip of surf-pounded Northland coast rates amongst the most well-known geographical features in Aotearoa. The euphonic Māori name, Te-Oneroa-a-Tōhē, The Long Beach of Tōhē, is more apt, considering the misnomer of ‘ninety miles’, as the beach is only 55 miles long (89km). However, many Te Araroa trampers will tell you that the trail’s northern gateway challenge can feel like 90.

N is also for…

Rakiura’s North-West Circuit where the mud is as prolific as the wildlife; and the namu sandfly – the bloodthirsty blackfly known to congregate in places of spectacular beauty.

Good things take time. Mountain biking the Old Ghost Road takes two or three days, walking requires five – and building the road took 130 years. In the 1880s, motivated more by optimism than sense, miners began building a dray road to connect the goldfields in Lyell and Mōkihinui. The unfinished, abandoned project became something of a ghost story until an 1886 map fell into the hands of some committed locals, who were big on optimism – and sense. They figured out how to connect either end through rugged terrain, raised millions, assembled a huge family of volunteers and got to work. They even saw off a hydroelectric dam project that would have flooded the northern end, including the airy historic track cut into the Mōkihinui Gorge.

Since opening in 2015, the Old Ghost Road has become a must-do – an unofficial Great Walk and a bucket-list ride for mountain bikers. If you like the sound of sweeping views from atop the Lyell Range or a cruisy single track descent to Stern Valley, book soon – come summer, the huts are usually full.

O is also for…

Olivine Wilderness, an unpredictable, remote place where the weather might make or break you; the Otehake River, a land of sandflies and hot pools; and Oroua River oases, where predator control is restoring Ngāti Kauwhata land.

Before people went bush in search of recreation, they went there in search of resources. Ngāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe and Waitaha people pioneered routes across Kā Tiritiri o te Moana, the Southern Alps, in pursuit of pounamu in West Coast rivers. When Europeans noticed gold in those rivers, they set out into these hills en masse, either following the pounamu trails or creating their own routes.

So next time you’re in places like Nōti Raureka Browning Pass, Nelson Lakes’ Burn Creek or the Coromandel’s Karangahake Gorge, spare a thought for the treasure hunters who came before.

P is also for…

Permolat, the West Coast hut-renovating organisation and its namesake, the aluminium used for track markers; and Pinnacles: Coromandel, Putangirua and Broken Axe among them.

Q is for Queen Charlotte Track

Pretty, bush-clad Meretoto/Ship Cove in the Marlborough Sounds, was favoured by Captain Cook as a resupply base for the Endeavour. It also became the country’s primary site of contact with Māori. Today, it’s the embarkation point for trampers and cyclists setting off on the Queen Charlotte Track. The Marlborough Sounds are drowned valleys, well known for their picturesque narrow ridgelines and maze of waterways and coves. The track threads through low saddles and varied forest with the comforts of civilisation never far away.

Q is also for…

Queenstown, the tourist gateway to the deep south where you hope never to have to buy replacement gear; quiet, the sound of … nothing; and quilts, the ultralighters’ dream.

New Zealand’s Great Walks catch the limelight and the foot traffic, but Mt Ruapehu’s 66km Round the Mountain loop is equally spectacular and a lot quieter. There’s a certain satisfaction in circumnavigating an alpine massif, experiencing its ecosystems, geology and topography and ending where you began.

A special aspect of this circuit is its wildness: the tracks are rough, the terrain is lumpy and not all streams are bridged. Ruapehu’s south-east quarter in particular is far from the mountain’s busy areas as it traverses the unique ashfields of the Rangipo Desert Te Onetapu, high above the Desert Road. The stark beauty here contrasts with the rich beech forest, shimmering tussock fields andthe sparkling Tama Lakes of the western quarter.

R is also for…

Rāhui, a restriction put in place by an area’s kaitiaki, often when someone dies; tītitipounamu rifleman and the pīwauwau rock wren, two of our smallest songbirds; and the Remutaka and Ruahine ranges.

‘Weetbix’, climbers call it – a suitably Kiwi nickname for greywacke, a distinctly Kiwi rock with a name of German origin (grauwacke). While the rock of many of the world’s alps is of firmer stuff, such as granite or limestone, much of the Southern Alps is stacked with sedimentary layers of sandstone origin. Among the terms geologists use to describe this hard, fine-grained but fractured rock are ‘texturally immature’ and ‘poorly sorted’.

This loose rock makes upward progress challenging, but it can be a blessing on a descent. Greywacke forms scree slopes and gullies of fine stone that move fluidly and forgivingly underfoot, enabling trampers to descend hundreds of metres in minutes.

S is also for…

Speargrass, beloved by weevils and best avoided by trampers; Shelter from the Storm, the landmark history of our hut network by Shaun Barnett, Rob Brown and Geoff Spearpoint; and swingbridges.

Travelling north along the Kāpiti Coast towards the plains of Manawatū, you might spy a bush-clad range above the foothills to the east. To the unacquainted, the Tararua Range doesn’t look much compared with southern mountains, except when winter snow highlights the tussocky tops. But a frequent visitor would easily identify skyline features: Hector, the Tararua Peaks, Aokaparangi and Dundas … names that are written into back country folklore. Along with the likes of Holdsworth, Kime, Waiohine and Bannister, these waypoints encapsulate the birthplace of tramping and hut culture in Aotearoa.

Those who know what’s between the sheer ridgelines and gorged rivers of these mountains often return to the intricate track network, the goblin forests, the aquamarine rivers and the miracle of a clear day on the tops. They also know the show-stopping wind, the disorienting mist and the sanctuary of the range’s plentiful huts.

Tramping took a muddy foothold in these temperamental mountains in the early 1900s, leading to the formation of New Zealand’s first tramping collective: Tararua Tramping Club. John Pascoe, Graeme Dingle, Shaun Barnett and Geoff Spearpoint are well-known names among the thousands who learned their outdoor craft within Tararua Forest Park.

T is also for…

Te Araroa, the long pathway from Cape Rēinga to Bluff; the Travers–Sabine Circuit, an 80km tramp deep into the high mountains of Nelson Lakes; the Tongariro Alpine Crossing, heralded as the best one-day trek in the country; and Taranaki Maunga, the third natural feature in New Zealand to be granted legal personhood.

Te Urewera is not a forest park, it’s a living being and the first ecosystem to be granted legal personhood. Kōkako call through mist as dense as rain that muffles the sound of movement. The manu, the mokomoko, the ngangara – myriad creatures living between the folds of green and grey. The ngahere offers food for the hungry, water for the thirsty and, for those who know, healing rongoa. But what do we give back?

Te Urewera is the ancestral home of Ngāi Tūhoe, where traditional knowledge is shared by hut wardens along the Lake Waikaremoana Great Walk, and where it pays to read ‘Te Kawa o Te Urewera’ – a people management document – before visiting. Because does a forest really need to be managed, or do we instead need to manage the impacts of humans?

U is also for…

Urchin to Umukarikari (U2U) in Kaimanawa Forest Park; undulating – or more likely, uphill; and Unknown Stream Hut.

There are few more simple pleasures than enjoying a view whilst doing one’s business. For all those magnificent huts, there is an equally grand list of loos from which to admire epic mountains, endless forests and churning rivers. There is time for contemplation, reflection and focus. The trials and tribulations of a day’s hard slog can melt away as you sit upon a thunderbox.

Knowing this, the best hut builders position the throne so that, with a swing of the door, the world opens up at your feet. Whether it’s the icy expanse of the Tasman Glacier from the loo at Caroline Hut, or the wilds of Fiordland from the MacKinnon Pass crapper, opportunity knocks (or maybe that’s the next person in line).

V is also for…

Volunteers, the unsung heroes of our great outdoors; and vegetable sheep, the alpine plant that’s actually a daisy.

Waiau Pass (1870m) isn’t the highest crossing on Te Araroa’s undulating path through the South Island’s ranges, but it’s possibly the most feared. For the southbounder, this remote pass is the apogee of a virtual symphony of tramping through some of the most scenic terrain on the trail to reach Rotopōhueroa/Lake Constance, where the track rises steeply to the pass which guards the head of the valley. During bad weather there’s a reason for its reputation. But when the view is clear, the wind breathless, and the pace unrushed, surefootedness and cautious route-finding will be rewarded with exceptional views.

W is also for…

Waitākere Ranges with their black-sand beaches and regenerating rainforest; whio blue duck, unique to New Zealand and fast-flowing rivers; and three-wire bridges.

Explorers, surveyors and musterers were a tough bunch; they probed the depths of the wilderness, which could be a lonely and unforgiving pastime for a man. It’s understandable then that they began to dream of company in the landscape around them.

Next time you gaze upon ‘The Amazons Breasts’ (Adams Wilderness Area) or ‘The Tits’ (Kāweka Forest Park), dwell for a second on these lonely adventurers.

There are, of course, the unintentionally x-rated places. Who hasn’t had an immature chuckle at names like ‘the Bonar Glacier’ (named after James Bonar, a prominent nineteenth-century Westlander) or the many shag rocks, streams and beaches. A heartfelt thanks to the New Zealand Geographic Board, the organisation that is responsible for official place names, for keeping tramping amusing.

X is also for…

Triple X Hut; xenicus, a genus of birds that includes pīwauwau rock wren; and Tasman’s Xenicus Peak and Otago’s Mt Xenicus.

When you go for a walk, your mind gets to go adventuring too. For some, this is soaking up the peace and silence; for others, it’s a chance to dive into fascinating yarns with friends and fellow trampers. You could be swapping tall tales of ‘epics’ or discussing topics you’d never normally explore. The best backcountry chats are often the unexpected ones – those conversations that come from sharing a hut with a stranger. After all, anyone you meet out here loves it too, and what better conversation starter is there?

Y is also for…

Yeat’s Ridge Hut is nestled in a red tussock-clad basin above the Toaroha River.

There are a couple of fundamental rules when tramping. The first is that everything’s better with snacks. The second is that mates who snore always drop off first. Always. What starts as a soft whimper slowly grows to a crescendo that would give a Husqvarna a run for its money. With more time in the hills, one can become a connoisseur. A Great Walk wheeze can be distinguished from a humble hut hum. A Westland whimper is altogether different from a Southland snort. Next time you head for the hills, remember to pack your earplugs.

Z is also for…

Zig-zag, the path of least resistance; Zit Saddle, in the West Coast’s Toaroha catchment; and Zealandia Fenceline Track, a stroll around the perimeter of the world’s first fully fenced ecosanctuary.

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us