Twenty-five years ago, two of New Zealand’s endangered and iconic species were in big trouble. There were just 51 kakapo left – the lowest the population has ever reached – and just over 100 takahe, confined to a dwindling mountain population and a few birds on offshore islands. But since then, both species have been saved from the brink of extinction: their populations tripled due to innovative and bold science-based conservation management.

Kakapo have just had the biggest breeding season in decades, with 33 chicks fledged from 47 hatchlings. This was the result of decades of development of conservation management techniques. Twenty-five years ago, kakapo could only be raised in nests, but now eggs can be artificially incubated and chicks hand-reared with a higher rate of success than occurs naturally.

In 1991, there were too many males, but application of conservation science theory has led to a correction of this sex bias by controlling female weights through supplementary feeding. Genetic techniques have been developed to assess relatedness, gender and paternity, and in 2009 artificial insemination was successful – a world-first for a wild bird species.

The Kakapo Recovery Programme has also become a world leader in its use of innovative technology. ‘Smart’ transmitters on every bird monitor health, mating and nesting, and allow birds to be weighed and fed automatically. Nests are monitored with remote cameras and proximity sensors, and a satellite system tells the team, from anywhere in the world, which kakapo have mated the previous night.

Takahe have also had their most successful breeding season in the last 25 years, with over 50 chicks fledged. This is driven by advances in captive breeding, with DOC’s takahe ‘farm’ near Te Anau increasing the entire population by up to 10 per cent a year. This has allowed the foundation of a large island ‘meta-population’: from just 15 individuals on three predator-free islands in 1991, to about 200 birds at 17 sites today, many open to the public. Careful genetic management and nest manipulation are behind this increase in productivity, with each pair provided at least one viable egg, and genetically-valuable pairs encouraged to re-nest.

Both kakapo and takahe face many threats, particularly those posed by inbreeding and disease, which must be overcome to ensure their survival. But a sign of the success of these conservation programmes is a new challenge: finding safe habitat in their historic range for the burgeoning populations.

– Andrew Digby is a DOC scientist leading the kakapo and takahe recovery programmes.

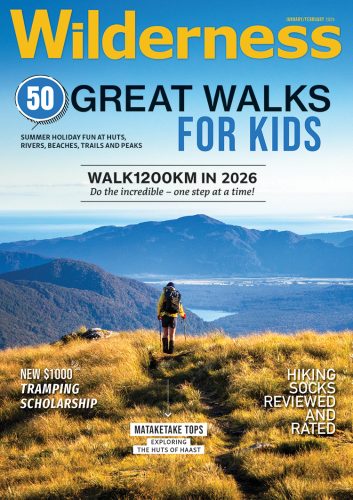

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us