When Don Stevens went into the Tararuas, his backpack stocked with some of his favourite sausages, the last thing he expected was to end up halfway down a ravine with shin bones sticking out of his leg.

Luckily, Stevens, 53, had a personal locator beacon, which he activated straight away. And, thanks to a network of new high-flying MEOSAR satellites, the signal was picked up in just four minutes, roughly an hour faster than the previous satellite location system.

Stevens, in addition to his regular jaunts in the Tararuas and trail-runs, is a sausage aficionado. His blog, Don’s Sausage Blog, details his love for and critiques of sausages from all over the country.

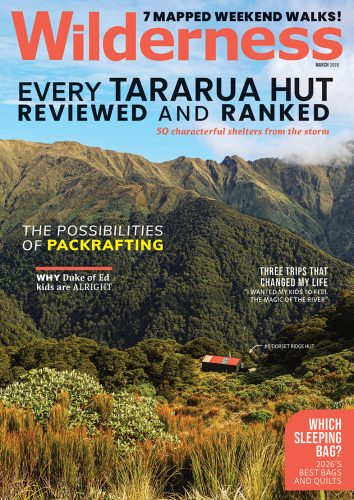

When calamity struck, Stevens was on a four-day tramp in Tararua Forest Park. He spends a lot of time in the area, and had carved out time for a solo tramp over ANZAC weekend. Two days into the trip, he was making his way down a steep ridgeline, coming off Girdlestone on his way to Tarn Ridge Hut, when he suddenly found himself somersaulting through the bush.

Stevens said he didn’t need to see the bones sticking out of his leg to know he was in trouble: he had sustained compound fractures of his tibia and fibula on his right leg. His tumble landed him about 40m from the track, and after turning on his beacon, he slowly dragged himself up the embankment to a place where he could get cell phone reception.

“Fortunately the puttees (or gaiters) on my boots meant that I could not see the exposed bones, however I could see the blood coming down the side of my boot,” Stevens recounts.

Reluctantly abandoning his snarlers, Stevens put weight on his knees and inched up the steep slope, which was covered in tussock, snow grass and loose rock.

“As I crawled upwards I was aware when the floppy lower leg was not supported by the ground and it hurt. I also had to roll over a couple of times. To do this I placed a hand on each side of my knee and then moved the stuffed leg over the good leg. It was a challenging manoeuvre.”

About an hour later, a helicopter circled nearby, spotted him, but flew away to refuel. Stevens called the police to give details of his location, a move that eventually helped another helicopter pick him up. It was dusk at that point, and Stevens was whisked away from the Tararuas just in time.

“Crawling up the side of the hill, I knew at the time it hurt like hell, but I just concentrated on my breathing,” Stevens said. “It’s almost like getting into a meditative state, and I think that really helped me.”

Without the rapid response time, Stevens likely would’ve spent a long, cold night in the Tararuas. The MEOSAR system is a network of 18 satellites orbiting the earth from about 20,000km. In October, 2015 a receiving station near Taupo was built as part of a joint project between Maritime NZ and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA). Since then, rescuers in New Zealand have had access to the information from AMSA, but only recently has the beacon information been transmitted to the receivers in New Zealand. Before MEOSARs, beacon signals were picked up by LEOSAR satellites, which orbit at about 800-1000km. Those satellites are still operating, and are still useful in transmitting signals that MEOSAR may have missed because of the coverage area. Because the 18 MEOSARs operate around the entire globe, their effectiveness currently relies on their positioning and proximity to New Zealand at any given time. When MEOSAR is fully operational, there will be a total of 48 satellites orbiting the earth.

The beacon Stevens was using was borrowed from his local Scout group, where he used to be a Scout leader. He said he always carries a beacon, and leaves his trip information with the Scouts.

“I’ve done first aid courses, and one of the things I know is that shock kicks in. And when shock kicks in, rational decisions can suffer,” Stevens said. “So, I said to myself, ‘You are not going to go into shock. You are going to remain alert, and focused.’ I mean, I knew I was in the crap – I was a long way from nowhere.”

Now, on the slow road to recovery, Stevens reflects on how fortunate he was to have his signal picked up so quickly.

“It’s amazing that all I did was break my leg,” Stevens said. “If I hadn’t hit the locator beacon, I’d be dead.”

34 years of inspiring New Zealanders to explore the outdoors. Don’t miss out — subscribe today.

Questions? Contact us